12 May 1789

William Wilberforce introduces a Bill to outlaw the slave trade

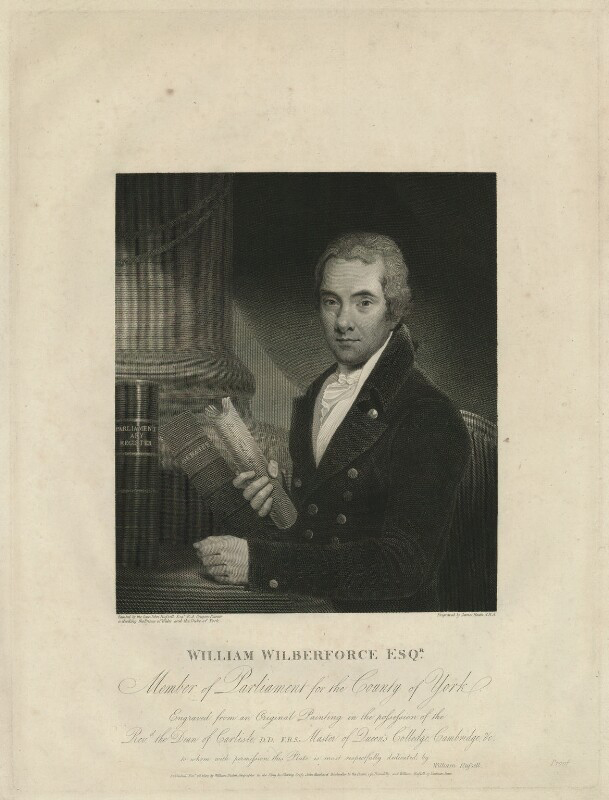

william wilberforce by James Heath after John Russell. line engraving, published 1807

NPG D37511 © National Portrait Gallery, London

WILLIAM WILBERFORCE’S involvement in the abolition movement was undoubtedly motivated by his desire to put his evangelical Christian principles into action. Along with fellow members of the Clapham Sect – a group of social reformers who attended Holy Trinity Church on Clapham Common – he was repulsed by the trade in human beings, the greed and avarice of the traders and the moral bankruptcy of the planter-owners. It may come as a surprise, then, to find that his speech introducing his Bill to outlaw the slave trade is virtually free of moralising. Instead, he takes a forensic, fact-based approach to dismantle the arguments of his opponents.

Although some of Wilberforce’s observations about the supposed barbarity of aspects of African society reflect the general prejudices of his age, his central question, ‘Does not every one see that a slave trade, carried on around her (Africa’s) coasts must carry violence and desolation to her very centre?’ goes right to the heart of an issue that is still tormenting the continent. It is the central theme of Walter Rodney’s influential 1972 book How Europe Underdeveloped Africa, for example.

He pours scorn on the testimony of Liverpool merchants who paint an idealised picture of conditions on a slave ship and reports how nearly one in five enslaved people die in transit or within a week of landing and that a further third die within a year from diseases contracted on the voyage. He dismisses the arguments of the planter lobby that enslavement of Africans is necessary for the running of West Indian plantations and sets out to prove the West Indies have nothing to fear from the total and immediate abolition of the trade. He argues that less intensive labour conditions, better diet and curtailing cruelty will lead to a natural increase in the African population, thus obviating the need for the slave trade.

Although Wilberforce first introduced his Bill to outlaw the slave trade in 1789, it was not until 1806 when Lord Grenville made a passionate speech arguing that the trade was “contrary to the principles of justice, humanity and sound policy” that a Bill to abolish the slave trade obtained a Parliamentary majority, with a majority of 41 votes to 20 in the Lords and a majority of 114 to 15 in the Commons. The Abolition of the Slave Trade Act entered the statute books the following year on 25 March.

Wilberforce’s speech in full

When I consider the magnitude of the subject which I am to bring before the House, a subject in which the interests, not of this country nor of Europe alone, but of the whole world and of posterity are involved, and when I think at the same time on the weakness of the advocate who has undertaken this great cause; when these reflections press upon my mind, it is impossible for me not to feel both terrified and concerned at my own inadequacy to such a task.

But when I reflect, however, on the encouragement which I have had, through the whole course of a long and laborious examination of this question, and how much candour I have experienced, and how conviction has increased within my own mind, in proportion as I have advanced in my labours; when I reflect, especially, that however averse any gentleman may now be, yet we shall all be of one opinion in the end; when I turn myself to these thoughts, I take courage. I determine to forget all my other fears, and I march forward with a firmer step in the full assurance that my cause will bear me out, and that I shall be able to justify upon the clearest principles, every resolution in my hand, the avowed end of which is, the total abolition of the slave trade.

I wish exceedingly, in the outset, to guard both myself and the House from entering into the subject with any sort of passion. It is not their passions I shall appeal to I ask only for their cool and impartial reason; and I wish not to take them by surprise, but to deliberate, point-by-point, upon every part of this question. I mean not to accuse any one, but to take the shame upon myself, in common, indeed, with the whole Parliament of Great Britain, for having suffered this horrid trade to be carried on under their authority. We are all guilty we ought all to plead guilty, and not to exculpate ourselves by throwing the blame on others; and I therefore deprecate every kind of reflection against the various descriptions of people who are more immediately involved in this wretched business.

In opening the nature of the slave trade, I need only observe, that it is found by experience to be just such as every man, who uses his reason, would infallibly conclude it to be. For my own part, so clearly am I convinced of the mischiefs inseparable from it, that I should hardly want any further evidence than my own mind would furnish, by the most simple deductions.

Facts, however, are now laid before the House. A report has been made by His Majesty’s Privy Council, which, I trust, every gentleman has read, and which ascertains the slave trade to be just such in practice as we know, from theory, it must be.

What should we suppose must naturally be the consequence of our carrying on a slave trade with Africa? With a country vast in its extent, not utterly barbarous, but civilised in a very small degree? Does any one suppose a slave trade would help their civilisation? Is it not plain that she must suffer from it? That civilisation must be checked; that her barbarous manners must be made more barbarous; and that the happiness of her millions of inhabitants must be prejudiced with her intercourse with Britain? Does not every one see that a slave trade, carried on around her coasts must carry violence and desolation to her very centre?

That in a continent just emerging from barbarism, if a trade in men is established, if her men are all converted into goods, and become commodities that can be bartered, it follows they must be subject to ravage just as goods are; and this, too, at a period of civilisation, when there is no protecting legislature to defend this their only sort of property, in the same manner as the rights of property are maintained by the legislature of every civilised country.

We see then, in the nature of things, how easily the practices of Africa are to be accounted for. Her kings are never compelled to war, that we can hear of, by public principles, by national glory, still less by the love of their people.

In Europe it is the extension of commerce, the maintenance of national honour, or some great public object, that is ever the motive to war with every monarch; but, in Africa, it is the personal avarice and sensuality, of their kings. These two vices of avarice and sensuality, the most powerful and predominant in natures thus corrupt, we tempt, we stimulate in all these African princes, and we depend upon these vices for the very maintenance of the slave trade.

Does the king of Barbessin want brandy? He has only to send his troops, in the night time, to burn and desolate a village; the captives will serve as commodities, that may be bartered with the British trader.

What a striking view of the wretched state of Africa does the tragedy of Calabar furnish! Two towns, formerly hostile, had settled their differences, and by an inter-marriage among their chiefs, had each pledged themselves to peace; but the trade in slaves was prejudiced by such pacifications, and it became, therefore, the policy of our traders to renew the hostilities. This, their policy, was soon put in practice, and the scene of carnage which followed was such, that it is better, perhaps, to refer gentlemen to the Privy Council’s report, than to agitate their minds by dwelling on it.

The slave trade, in its very nature, is the source of such kind of tragedies; nor has there been a single person, almost, before the Privy Council, who does not add something by his testimony to the mass of evidence upon this point. Some indeed, of these gentlemen, and particularly the delegates from Liverpool, have endeavoured to reason down this plain principle: some have palliated it; but there is not one, I believe, who does not more or less admit it. Some, nay most, I believe, have admitted the slave trade to be the chief cause of wars in Africa.

Mr. Penny, a Liverpool delegate, has called it the concurrent cause; some confess it to be sometimes the cause, but argue that it cannot often be so. Here I must make one observation, which I hope may be done without offence to any one, and which I do, once for all, though it applies equally to many other evidences upon this subject. I mean to lay it down as my principle, that evidences, and especially interested evidences, are not to be judges of the argument. In matters of fact, of which they speak, I admit their competency. I mean not to suspect their credibility with respect to any thing they see or hear, or themselves personally know; but, in reasoning about causes and effects, I hold them to be totally incompetent.

So far, therefore, from submitting to their conclusions in this respect, I utterly discard them. I take their premises readily and fairly; but, upon these premises, I must judge for myself. And the House, I trust, nay, I perfectly well know, will in like manner judge for itself. Confident assertions, therefore, not of facts but of supposed consequences of facts, however pressed by the Liverpool delegates, or any other interested persons, go for nothing in my estimation. And it is necessary that Parliament should proceed upon this principle, as well in this as every other public question in which interested evidences must be examined.

Thus the African committee have reported that very few enormities, in their opinion, can have been practiced in Africa. Because, in forty years, only two complaints have been made to them. I admit the fact to them undoubtedly. But, I trust gentlemen will judge for themselves, whether Parliament is to rest satisfied that there are no abuses in Africa, in spite of all the positive proofs of so many witnesses on the spot to the contrary. Whether, for instance, Mr. Wardstrom’s evidence, Dr. Spaerman’s, Captain Hill’s, are to go for nothing, many of whom either saw the battles, were told by the kings themselves, that it was for the sake of slaves they went to battle, or conversed with a variety of prisoners taken by these means.

In truth as inquiry from the African committee whether any foul play prevails in Africa, is somewhat like an application to the Custom-house officers to know whether any smuggling is going on. The officer may tell you that very few seizures are made, and very few frauds come to his knowledge. But does it follow that Parliament must agree to all the reasonings of the officer? And though smuggling be ever so notorious through the land, must agree there is no smuggling, because the officer reports that he makes very few seizures, and seldom hears of it?

I will not believe, therefore, the mere opinions of African traders, concerning the nature and consequences of the slave trade. It is a trade in its principle most inevitably calculated to spread disunion among the African princes, to sow the seeds of every mischief, to inspire enmity, to destroy humanity. And it is found in practice, by the most abundant testimony, to have had the effect in Africa of carrying misery, devastation, and ruin wherever its baneful influence has extended.

Having now disposed of the first part of this subject, I must speak of the transit of the slaves in the West Indies. This I confess, in my own opinion, is the most wretched part of the whole subject. So much misery condensed in so little room is more than the human imagination had ever before conceived. I will not accuse the Liverpool merchants. I will allow, them, nay, I will believe them, to be men of humanity. And I will therefore believe, if it were not for the multitude of these wretched objects, if it were not for the enormous magnitude and extent of the evil which distracts their attention from individual cases, and makes them think generally, and therefore less feelingly on the subject, they never would have persisted in the trade.

I verily believe, therefore, if the wretchedness of any one of the many hundred negroes stowed in each ship could be brought before their view, and remain within the sight of the African merchant, that there is no one among them whose heart would bear it. Let any one imagine to himself six or seven hundred of these wretches chained two and two, surrounded with every object that is nauseous and disgusting, diseased, and struggling under every kind of wretchedness! How can we bear to think of such a scene as this? One would think it had been determined to heap on them all the varieties of bodily pain, for the purpose of blunting the feelings of the mind. And yet, in this very point, to show the power of human prejudice, the situation of the slaves has been described by Mr. Norris, one of the Liverpool delegates, in a manner which, I am sure will convince the House how interest can draw a film over the eyes, so thick, that total blindness could do no more; and how it is our duty therefore to trust not to the reasonings of interested men, or to their way of colouring a transaction.

“Their apartments,” says Mr. Norris, “are fitted up as much for their advantage as circumstances will admit. The right ankle of one, indeed, is connected with the left ankle of another by a small iron fetter, and if they are turbulent, by another on their wrists. They have several meals a day; some of their own country provisions, with the best sauces of African cookery; and by the way of variety, another meal of pulse etc. according to European taste. After breakfast they have water to wash themselves, while their apartments are perfumed with frankincense and lime juice. Before dinner, they are amused after the manner of their country. The song and the dance are promoted,” and, as if the whole was really a scene of pleasure and dissipation, it is added that games of chance are furnished. “The men play and sing, while the women and girls make fanciful ornaments with beads, which they

are plentifully supplied with.” Such is the sort of strain in which the Liverpool delegates, and particularly Mr. Norris, gave evidence before the Privy Council.

What will the House think when, by the concurring testimony of other witnesses, the true history is laid open. The slaves, who are sometimes described as rejoicing at their captivity, are so wrung with misery at leaving their country, that it is the constant practice to set sail in the night, lest they should be sensible of their departure. The pulse which Mr. Norris talks of are horse beans; and the scantiness, both of water and provision, was suggested by the very legislature of Jamaica, in the report of their committee, to be a subject that called for the interference of Parliament. Mr. Norris talks of frankincense and lime juice, when the surgeons tell you the slaves are stowed so close that there is not room to tread among them, and when you have it in evidence from Sir George Younge, that even in a ship which wanted 200 of her complement, the stench was intolerable.

The song and the dance, says Mr. Norris, are promoted. It had been more fair, perhaps, if he had explained that word promoted. The truth is, that for the sake of exercise, these miserable wretches, loaded with chains, oppressed with disease and wretchedness, are forced to dance by the terror of the lash, and sometimes by the actual use of it. “I,” says one of the other evidences, “was employed to dance the men, while another person danced the women.” Such, then, is the meaning of the word promoted. And it may be observed too, with respect to food, that an instrument is sometimes carried out, in order to force them to eat, which is the same sort of proof how much they enjoy themselves in that instance also. As to their singing, what shall we say when we are told that their songs are songs of lamentation upon their departure which, while they sing, are always in tears, insomuch that one captain (more humane as I should conceive him, therefore, than the rest) threatened one of the women with a flogging, because the mournfulness of her song was too painful for his feelings.

In order, however, not to trust too much to any sort of description, I will call the attention of the House to one species of evidence, which is absolutely infallible. Death, at least, is a sure ground of evidence, and the proportion of deaths will not only confirm, but, if possible, will even aggravate our suspicion of their misery in the transit. It will be found, upon an average of all the ships of which evidence has been given at the Privy Council, that, exclusive of those who perish before they sail, not less than 12 1/2 per cent perish in the passage. Besides these, the Jamaica report tells you that not less than 4 1/2 per cent die on shore before the day of sale, which is only a week or two from the time of landing. One-third more die in the seasoning, and this in a country exactly like their own, where they are healthy and happy, as some of the evidences would pretend. The diseases, however, which they contract on shipboard, the astringent washes, which are to hide their wounds, and the mischievous tricks used to make them up for sale, are, as the Jamaica report says, (a most precious and valuable report, which I shall often have to advert to) one principal cause of this mortality. Upon the whole, however, here is a mortality of about 50 per cent, and this among negroes who are not bought unless quite healthy at first, and unless (as the phrase is with cattle) they are sound in wind and limb.

How then can the House refuse its belief to the multiplied testimonies, before the Privy Council, of the savage treatment of the negroes in the middle passage? Nay, indeed, what need is there of any evidence? The number of deaths speaks for itself, and makes all such inquiry superfluous. As soon as ever I had arrived thus far in my investigation of the slave trade, I confess to you, sir, so enormous, so dreadful, so irremediable did its wickedness appear, that my own mind was completely made up for the abolition. A trade founded in iniquity, and carried on as this was, must be abolished, let the policy be what it might, let the consequences be what they would, I from this time determined that I would never rest till I had effected its abolition.

Such enormities as these having once come within my knowledge I should not have been faithful to the sight of my eyes, to the use of my senses and my reason, if I had shrunk from attempting the abolition. It is true, indeed, my mind was harassed beyond measure. For when West-India planters and merchants reported it upon me that it was the British Parliament had authorized this trade, when they said to me, “It is your acts of Parliament, it is your encouragement, it is faith in your laws, in your protection, that has tempted us into this trade, and has now made it necessary to us.” It became difficult, indeed, what to answer; if the ruin of the West-Indies threatened us on the one hand, while this load of wickedness pressed upon us on the other, the alternative, indeed, was awful.

It naturally suggested itself to me, how strange it was that providence, however mysterious in its ways, should so have constituted the world, as to make one part of it depend for its existence on the depopulation and devastation of another. I could not therefore, help distrusting the arguments of those, who insisted that the plundering of Africa was necessary for the cultivation of the West Indies. I could not believe that the same Being who forbids rapine and bloodshed, had made rapine and bloodshed necessary to the well-being of any part of his universe. I felt a confidence in this principle, and took the resolution to act upon it. Soon, indeed, the light broke in upon me. The suspicion of my mind was every day confirmed by increasing information, the truth became clear. The evidence I have to offer upon this point is now decisive and complete. And I wish to observe with submission, but with perfect conviction of heart what an instance is this, how safely we may trust the rules of justice, the dictates of conscience, and the laws of God in opposition even to the seeming impolicy of these eternal principles.

I hope now to prove, by authentic evidence, that in truth the West Indies have nothing to fear from the total and immediate abolition of the slave trade. I will enter minutely into this point, and I do entreat the most exact attention of gentlemen most interested in this part of the question. The resolutions I have to offer are many and particular, for the purpose of bringing each point under a separate discussion. And thus I hope it will be shown that Parliament is not disposed to overlook the interests of the West Indies.

The principle, however, upon which I found the necessity of abolition is not policy but justice; but though justice be the principle of the measure, yet, I trust, I shall distinctly prove it to be reconcilable with our truest political interest.

In entering therefore into the next branch of my subject, namely the state of slaves in the West Indies, I would observe that here, as in many other cases, it happens that the owner of principal generally sends out the best orders imaginable, which the manager upon the spot may pursue or not, as he pleases.

I do not accuse even the manager of any native cruelty, he is a person made like ourselves (for nature is much the same in all persons) but it is habit that generates cruelty. This man looking down upon his slaves as a set of beings of another nature from himself, can have no sympathy for them, and it is sympathy, and nothing else than sympathy, which, according to the best writers and judges of the subject, is the true spring of humanity.

Let us ask then what are the causes of the mortality in the West Indies.

In the first place, the disproportion of sexes; an evil, which, when the slave trade is abolished, must in the course of nature cure itself.

In the second place, the disorders contracted in the middle passage. And here let me touch upon an argument for ever used by the advocates for the slave trade, the fallacy of which is no where more notorious that in this place. It is said to be the interest of the traders to use their slaves well; the astringent washes, escharotics, and mercurial ointments, by which they are made up for sale, is one answer to this argument. In this instance, it is not their interest to use them well. And although in some respects self-interest and humanity will go together, yet unhappily through the whole progress of the slave trade, the very converse of this principle is continually occurring.

A third cause of deaths in the West Indies is excessive labour joined with improper food. I mean not to blame the West Indians, for this evil springs from the very nature of things.

In this country the work is fairly paid for and distributed among our labourers according to the reasonableness of things. And if a trader or manufacturer finds his profits decrease, he retrenches his own expenses, he lessens the number of his hands, and every branch of trade fins its proper level. In the West Indies the whole number of slaves remains with the same master. Is the master pinched in his profits, the slave allowance is pinched in consequence. For as charity begins at home, the usual gratification of the master will never be given up, so long as there is a possibility of making the retrenchment from the allowance of the slaves. There is therefore a constant tendency to the very minimum with respect to slaves’ allowance. And if, in any one hard year, the slaves get through upon a reduced allowance, from the very nature of man it must happen, that this becomes a precedent upon other occasions; nor is the gradual destruction of the slave a consideration sufficient to counteract the immediate advantage and profit that is got by their hard usage.

Here then we perceive again how the argument of interest fails also with respect to the treatment of slaves in the West Indies. Interest is undoubtedly the great spring of action in the affairs of mankind. But it is immediate and present, not future and distant interest, however real, that is apt to actuate us. We may trust that men will follow their interest when present impulse and interest correspond, but not otherwise. That this is a true observation may be proved by everything in life. Why do we make laws to punish men? It is their interest to be upright and virtuous, without these laws. But there is a present impulse continually breaking in upon their better judgment; an impulse contrary to their permanent and known interest, which it is not even in the power of all our laws sufficiently to restrain.

It is ridiculous to say, therefore, that men will be bound by their interest, when present gain or when the force of passion is urging them. It is no less ridiculous than if we were to say that a stone cannot be thrown into the air, nor any body move along the earth, because the great principle of gravitation must keep them for ever fast. The principle of gravitation is true. And yet, in spite of it, there are a thousand motions which bodies may be driven into continually, and upon which we ought as much to reckon as on gravitation itself.

This principle, therefore, of self-interest, which is brought in to answer every charge of cruelty throughout the slave trade, is not to be thus generally admitted. That the allowance is too short in the West Indies appears very plain also from the evidence. The allowance in the prisons I conceive must be an under allowance, and yet I find it to be somewhat less that this.

Dr. Adair (who is not very favourable to my propositions, and who by way of evidence, wrote a sort of pamphlet against me to the Privy Council) has said that even he thinks their food at crop-time too little. And I observe from Governor Ord’s statement that he accounts for their being more healthy at a less favourable seasons of the year, from their being better fed at the unfavourable season.

Another cause of the mortality of slaves is the dreadful dissoluteness of their manners. Here it might be said that self-interest must induce the planters to wish for some order and decency around their families. But in this case also it is slavery itself that is the mischief.

Slaves, considered as cattle, left without instruction, without any institution of marriage, so depressed as to have no means almost of civilization, will undoubtedly be dissolute. And, until attempts are made to raise them a little above their present situation, this source of mortality will remain.

Some evidences, indeed, have endeavoured to disprove that there is any particular wretchedness among the slaves in the West Indies. Admiral Barrington tells you he has seen them look so happy that he has sometimes wished himself one of them. I conceive that in a case like this an admiral’s evidence is perhaps the very worst that can be taken. It is as if a king were to judge of the private happiness of his soldiers by seeing them on a review day. The sight of the admiral would, no doubt, exhilarate their faces. He would see them in their best clothes, and they, perhaps, might hope for a few of the crumbs which fell from the admiral’s table. But does it follow that there is no hard treatment of slaves in the West Indies? The admiral’s wish to be one of these slaves himself proves perhaps that he was in an odd humour at the moment, or perhaps it might mean (for all the world knows his humanity) that he could wish to alleviate their sufferings by taking a share upon himself. But at least it proves nothing of their general treatment. And, at any rate, it is but a negative proof which affects not the other evidences to the contrary.

It is now to be remarked that all these causes of mortality among the slaves do undoubtedly admit of a remedy, and it is the abolition of the slave trade that will serve as this remedy.

When the manager shall know that a fresh importation is not to be had from Africa, and that he cannot retrieve the deaths he occasions by any new purchases, humanity must be introduced; an improvement in the system of treating them will thus infallibly be effected, an assiduous care of their health and of their morals, marriage institutions, and many other things, as yet little thought of, will take place; because they will be absolutely necessary.

Births will thus increase naturally instead of fresh accessions of the same negroes from Africa, each generation will then improve upon the former, and thus will the West Indies themselves eventually profit by the abolition of the slave trade.

But, sir, I will show by experience already had, how the multiplication of slaves depends upon their good treatment. All sides agree that slaves are much better treated now than they were thirty years ago in the West Indies, and that there is every day a growing improvement. I will show, therefore, by authentic documents, how their numbers have increased (or rather how the decrease has lessened) in the same proportion as the treatment has improved.

There were in Jamaica in the year 1761, 147,000 slaves. In the year 1787, there were 256,000 slaves. In all this period of 26 years, 165,000 were imported, which would be upon an average 2150 per annum, there being, on an average of the whole 26 years, 1 1-15th per cent yearly diminution of the number of slaves on the island.

In fact, however, I find that the diminution in the first period, when they were the worst used was 2 1/4 per cent. In the next 7 years it was 1 per cent. And the average of the last period is 3-5ths per cent. It should also be observed that there has lately been, on account of the war, a much more than ordinary diminution, which was the case also in the former war, besides that 15,000 have been destroyed by the late famine and hurricanes.

Upon these premises I ground a conclusion, that in Jamaica there is at this time an actual increase of population among the slaves begun. It may fairly be presumed, that since the year 1782, this has been the case, and that the births by this time exceed the deaths by about 1,000 or 1,100 per annum.

It is true the sexes are not altogether equal. But this difference is so small that if the proper number of women were added, the births to be expected in consequence would be no more than 300 per annum, which shows this to be a matter of little consequence.

In the island of Barbados, the case is nearly the same as Jamaica. In St. Christopher’s there are 9,600 females, and 10,300 males. So that an increase by birth if the treatment is tolerable, may fairly be expected. In Dominica, Governor Ord writes, that there is a natural increase, though it is yet inconsiderable, and though the smuggling in that island makes it not appear so favourably. In Nevis there are absolutely five women to four men. In Antigua, the epidemical disorders have lately cut off 1-4th or 1-5th of the negroes; but this cannot be expected to return, especially when the grand cause of epidemical disorders is removed. In Bermuda and the Bahamas there is an actual increase. In Montserrat there is much the same decrease as there has been in Jamaica, which is to be accounted for by the emigrations from that island.

Such, sir, is the state of the negroes in our West India islands. And it is not only founded upon authentic documents from thence, but it is also confirmed by a variety of other proofs.

Mr. Long, whose works are looked up to as a sort of West India gospel upon these subjects, lays it down as a principle, that when there are two negroes upon an island to three hogsheads of sugar, the work for them will be so moderate, as to ensure a natural increase; and there is now much more than this proportion.

It can be proved too, that a variety of individuals by good usage have more than kept up their stock. But, allowing even the number of negroes to be deficient, still there are many other resources to be had – the waste of labour which now prevails, the introduction of the plough and other machinery, the division of work, which in free and civilized countries is the grand source of wealth, the reduction of the number of negro servants, of whom not less than from 20 to 40 are kept in ordinary families.

All these I touch upon merely as hints, to show that the West Indies are not bereaved of all the means of cultivation their estates, as some persons have feared.

But, sir, even if these suppositions are all false and idle, if every one of these succedanea should fail, I still do maintain that the West India planters can and will indemnify themselves by the increased price of their produce in our market; a principle which is so clear, that in questions of taxation, or any other question of policy, this sort of argument would undoubtedly be admitted.

I say, therefore, that the West Indians who contend against the abolition, are non-suited in every part of the argument. Do they say that importations are necessary? I have shown that the very numbers in the gang may be kept up by procreation. Is this denied? I say, the plough, horses, machinery, domestic slaves, and all the other succedanea will supply the deficiency. It is persisted that the deficiency can in no way be supplied, and that the quantity of produce must diminish? I then revert to that irrefragable argument that the increase of price will make up their loss, and is a clear ultimate security.

I have in my hand the extract from a pamphlet which states in very dreadful colours what thousands and tens of thousands will be ruined; how our wealth will be impaired; one third of our commerce cut off for ever; how our manufactures will droop in consequence, our land-tax will be raised, our marine destroyed, while France, our natural enemy and rival, will strengthen herself by our weakness.

[A cry of assent being heard from several parts of the House, Mr. Wilberforce added,]

I beg, sir, that gentlemen will not mistake me. The pamphlet from whence this prophecy is taken was written by Mr. Glover in 1774, on a very different occasion; and I would therefore ask gentlemen, whether it is indeed fulfilled? Is our wealth decayed, our commerce cut off? Are our manufactures and our marine destroyed? Is France raised upon our ruins? On the contrary. Do we not see by the instance of this pamphlet, how men in a desponding moment will picture to themselves the most gloomy consequences, from causes by no means to be apprehended?

We are all, in this respect, apt sometimes to be carried away by a frightened imagination. Like poor negroes, we are all in our turn, subject to Obiha (Obeah); and when we have an interest to bias us, we are carried away ten thousand times more. The African merchants told us last year that if less than two men to a ton were to be allowed, the trade could not continue. Mr. Tarleton, instructed by the whole trade of Liverpool, declared the same: told us that commerce would be ruined and our manufactures would migrate to France.

We have petitions on the table from the manufacturers, but I believe they are not dated at Havre or any port in France. And yet it is certain that out of 20 ships last year from Liverpool, not less than 13 carried this very ruinous proportion of less than two to a ton. It is said that Liverpool will be undone. “The trade,” says Mr. Dalziel, “at this time hangs upon a thread, and the smallest matter will overthrow it.”

I believe, indeed, the trade is a losing trade to Liverpool at this time. It is a lottery in which some men have made large fortunes, chiefly by being their own insurers, while others follow the example of a few lucky adventurers and lose money by it. It is absurd to say, therefore, that Liverpool will be ruined by the abolition, or that it will feel the difference very sensibly, since the whole outward-bound tonnage of the slave trade amounts only to one-fifteenth of the outward-bound tonnage of Liverpool.

We ought to remember also, that the slave trade actually was suspended during some years of the war; nor did any calamity follow from it.

As to shipping, our fisheries and other trades will furnish so many innocent and bloodless ways of employing vessels that no mischief need be dreaded from this quarter.

The next subject which I shall touch upon is the influence of the slave trade upon our marine; and instead of being a benefit to our sailors, as some have ignorantly argued, I do assert it is their grave. The evidence upon the point is clear; for, by the indefatigable industry and public spirit of Mr. Clarkson, the muster rolls of all the slave ships have been collected and compared with those of other trades. And it appears in the result that more sailors die in one year in the slave trade than die in two years in all our other trades put together.

It appears by the muster roll, to 88 slave ships which sailed from Liverpool in 1787, that the original crews consisted of 3,170 sailors. Of these only 1,428 returned: 642 died or were lost, and 1,100 were discharged on the voyage or deserted either in Africa or the West Indies. It appeared to me for a long time unaccountable how so vast a proportion of these sailors should leave their ships in the West Indies. But I shall quote here a letter from Governor Parry at Barbados to Lord Sydney, dated May 13, 1788, transmitting two petitions, and which explains this difficulty.

“To the African trade on the coast I cannot venture to speak, not being sufficiently acquainted with it; but am fearful such monstrous abuses have crept into it, as to make the interference of the British legislature absolutely necessary; and have to lament that it falls to my lot to possess your lordship with the unpleasing information contained in the enclosed petitions, which is fully demonstrative of the shameful practices carried on in that unnatural commerce.”

He then speaks of having seen Captain Bibby, who is the person mentioned in the following petitions, though the other captain had endeavoured to prevent it, and, he says, he has sent back the pawns (mentioned also in the petition) to their enraged parents, adding,

“That I cannot help having my suspicions; and I was yesterday told, that he had private instructions from the petitioners not to present the petitions to me, if Bibby would quietly resign the pawns; which leads me to believe there was a general combination in these unwarrantable practices among all the masters of the vessels then in Cameroons river.”

He then comes to the subject of the British sailors.

“Your lordship,” says he, “is perfectly informed of the nefarious practices of the African trade, and the cruel manner in which the greater number of the masters treat their seamen. There is scarcely a vessel in that trade that calls at Barbados, from which I have not a complaint made to me, either by the master of the seamen; but more frequently the latter, who are often shamefully used; for the African traders at home being obliged to send out their ships very strong handed, as well from the unhealthiness of the climate, as the necessity of guarding the slaves, soon feel the expense of seamen’s wages.

And as soon as they come amongst these islands, and all danger of insurrection is removed, the masters quarrel with their seamen, upon the most frivolous pretences, and turn them on shore on the first island they stop at, sometimes with, and sometimes without paying them their wages; and Barbados being windward station, had generally a large proportion of these men thrown in upon her; and sorry am I to say, that many of these valuable subjects are, from sickness and the dire necessity of entering into foreign employ for maintenance, lost to the British nation.”

Thus do we see how Mr. Clarkson’s account of the muster rolls is verified, and why it is that so vast a proportion of sailors in the slave ships are lost to this country. But let us touch also on the petitions which Governor Parry speaks of. It seems that Captain Bibby, before mentioned, had carried off from Africa 30 of the king’s children and relations left in pawn with him, who retaliated by seizing five English captains. These captains dispatch a vessel with petitions to Governor Parry to send back the king’s sons in order to their own release. Now, sir, let us mark the style of these petitions.

“I, James M’Gauty, I, William Willoughby, etc. being on shore on the execution of our business, were seized by a body of armed natives, who lay in ambush in order to take us.”

What villains must these Africans be, to seize so designedly such friends as the British subjects, and this merely with a view to get back their children!

“This,” says the petition, “they effected, and dragged us to their town, where they treated us in a most savage and barbarous manner, and loaded us with irons.”

Observe, sir, the indignant spirit of these captains; British freemen to be loaded with irons! White men in custody of these barbarous negroes? But what was the cause of this abominable outrage?

“On account,” say they, “of the imprudent behaviour of Captain Robert Bibby,” – but what was the imprudence? “who carried off 30 pawns, who were the king’s and traders’ sons, daughters, and relations.”

Here, then, we have a picture of the equitable spirit in which this trade is carried on. These princes and chiefs, who, by Captain Bibby’s imprudence, had lost all their families and children, propose, however, to satisfy every demand, and to give these captains their liberty, provided only they may have their children back again.

“But,” say two of the captains, “We, finding that we could not comply with their extravagant conditions, did endeavour to regain our liberty, which we effected. But we verily believe, that our respective voyages are entirely ruined, the natives being determined to make no farther trade with either of us, nor pay the above debts, until their sons, daughters, etc are returned, and debarring us of wood, water, or any country provisions. Therefore, we shall be forced to leave the river immediately and, on that account, we think our voyages ruined, as before.”

It has been urged by some persons, in proof of the wicked barbarity of these kings and chiefs, that they pawn their own children, from which it is concluded that they feel no sort of affection for them, and therefore deserve all the evils which we inflict upon them.

The contrary is in truth the case. For the captains, knowing the affection they have for their relations, are willing to take them as hostages for very considerable debts, and are sensible of their ideal value, though the real value is trifling. And the scene which I have just laid before you, very fairly shows both the general spirit of our captains, and the wretched situation to which our commerce has reduced these African princes.

And if, sir, at the very moment when Parliament was known to be inquiring into this trade, these abuses are thus boldly persisted in, how can we suppose that any regulations or any palliatives can overcome these enormities, and justify our continuance of the trade?

It is true, the African committee hear little of the matter; for we find that even these captains, who were in prison, instructed the bearer of their petition not to apply to Governor Parry, except in the last necessity, but merely to get back the king’s sons, meaning quietly to compromise matters with Captain Bibby; and if it were not for the vigilance of Governor Parry, the truth would never have come out.

In like manner, we find that although very few sailors, when they come to Liverpool, go into an expensive prosecution of their captains, yet Governor Parry hears of complaints against them every day. And we find that Justice Otley, in the island of St. Vincent, were law is cheap, both hears their grievances and redresses them.

There is one other argument, in my opinion a very weak and absurd one, which many persons, however, have much dwelt upon. I mean that, if we relinquish the slave trade, France will take it up.

If the slave trade be such as I have described it, and if the House is also convinced of this, if it be in truth both wicked and impolitic, we cannot wish a greater mischief to France than that she should adopt it. For the sake of France, however, and for the sake of humanity, I trust, nay, I am sure, she will not. France is too enlightened a nation to begin pushing a scandalous as well as ruinous traffic, at the very time when England sees her folly and resolves to give it up.

It is clearly no argument whatever against the wickedness of the trade, that France will adopt it. For those who argue thus may argue equally that we may rob, murder, and commit any crime, which any one else would have committed, if we did not. The truth is that by our example we shall produce the contrary effect. If we refuse the abolition, we shall lie, therefore, under the twofold guilt of knowingly persisting in this wicked trade ourselves, and, as far as we can, of inducing France to do the same.

Let us, therefore, lead the way. Let this enlightened country take precedence in this noble cause, and we shall soon find that France is not backward to follow, nay, perhaps to accompany our steps. If they should be mad enough to adopt it, they will have every disadvantage to cope with. They must buy the negroes much dearer than we; the manufacturers they sell, must probably be ours; and expensive floating factory, ruinous to the health of sailors, which we have hitherto maintained, must be set up. And, after all, the trade can serve only as a sort of Gibraltar, upon which they may spend their strength, while the productive branches of their commerce must in proportion be neglected and starved.

But I have every ground for believing that the French will not be thus wicked and absurd. M. Necker, the enlightened minister of that country, a man who has introduced moral and religious principles into government, more than has been common with many ministers, has actually recorded his abhorrence of the slave trade. He has, under his own hand in his publication of the finances, pledged himself, as it were, to the abolition, and it is impossible that a man can be so lost to all sense of decency and common consistency of character as not to forward, by every influence in his power, a cause in which he has so publicly declared himself.

There is another anecdote which I mention here with pleasure, which is that the king of France very lately being requested to dissolve a society set up in France, for the abolition of the slave trade, made answer, “That he certainly should not, for that he was very glad it existed.”

I believe, sir, I have now touched upon all the objections of any consequence, which are made to the abolition of this trade.

When we consider the vastness of the continent of Africa; when we reflect how all other countries have for some centuries past been advancing in happiness and civilization; when we think how in this same period all improvement in Africa has been defeated by her intercourse with Britain; when we reflect it is we ourselves that have degraded them to that wretched brutishness and barbarity which we now plead as the justification of our guilt; how the slave trade has enslaved their minds, blackened their character, and sunk them so low in the scale of animal beings that some think the apes are of a higher class, and fancy the orangutan has given them the go-by. What a mortification must we feel at having so long neglected to think of our guilt, or to attempt any reparation!

It seems, indeed, as if we had determined to forbear from all interference until the measure of our folly and wickedness was so full and complete, until the impolicy which eventually belongs to vice, was become so plain and glaring that not an individual in the country should refuse to join in the abolition; it seems as if we had waited until the persons most interested should be tired out with the folly and nefariousness of the trade, and should unite in petitioning against it.

Let us then make such amends as we can for the mischiefs we have done to that unhappy continent.

Let us recollect what Europe itself was no longer ago than three or four centuries. What if I should be able to show this House that in a civilized part of Europe, in the time of our Henry VII, there were people who actually sold their own children? What if I should tell them that England itself was that country? What if I should point out to them that the very place where this inhuman traffic was carried on was the city of Bristol? Ireland at that time used to drive a considerable trade in slaves with these neighbouring barbarians; but a great plague having infested the country, the Irish were struck with a panic, suspected (I am sure very properly) that the plague was a punishment sent from Heaven, for the sin of the slave trade, and therefore abolished it.

All I ask, therefore, of the people of Bristol is, that they would become as civilized now as Irishmen were four hundred years ago. Let us put an end at once to this inhuman traffic. Let us stop this effusion of human blood. The true way to virtue is by withdrawing from temptation. Let us then withdraw from these wretched Africans those temptations to fraud, violence, cruelty, and injustice, which the slave trade furnishes.

Wherever the sun shines, let us go round the world with him, diffusing our beneficence; but let us not traffic, only that we may set kings against their subjects, subjects against their kings, sowing discord in every village, fear and terror in every family, setting millions of our fellow-creatures a hunting each other for slaves, creating fairs and markets for human flesh, through one whole continent of the world, and, under the name of policy, concealing from ourselves all the baseness and iniquity of such a traffic.

Why may we not hope, ere long, to see Hans-towns established on the coast of Africa as they were on the Baltic ? It is said the Africans are idle, but they are not too idle, at least, to catch one another. Seven hundred to one thousand tons of rice are annually bought of them. By the same rule, why should we not buy more? At Gambia one thousand of them are seen continually at work. Why should not some more thousands be set to work in the same manner? It is the slave trade that causes their idleness and every other mischief. We are told by one witness, “They sell one another as they can.” And while they can get brandy by catching one another, no wonder they are too idle for any regular work.

I have one word more to add upon a most material point. But it is a point so self-evident that I shall be extremely short.

It will appear from everything which I have said, that it is not regulation, it is not mere palliatives, that can cure this enormous evil. Total abolition is the only possible cure for it.

The Jamaica report, indeed, admits much of the evil, but recommends it to us so to regulate the trade, that no persons should be kidnapped or made slaves contrary to the custom of Africa. But may they not be made slaves unjustly, and yet by no means contrary to the custom of Africa? I have shown they may; for all the customs of Africa are rendered savage and unjust through the influence of this trade; besides, how can we discriminate between the slaves justly and unjustly made? Can we know them by physiognomy? Or, if we could, does any man believe that the British captains can, by any regulation in this country, be prevailed upon to refuse all such slaves as have not been fairly, honestly, and uprightly enslaved? But granting even that they should do this, yet how would the rejected slaves be recompensed? They are brought, as we are told, from three or four thousand miles off, and exchanged like cattle from one hand to another, until they reach the coast.

We see then that it is the existence of the slave trade that is the spring of all this

internal traffic, and that the remedy cannot be applied without abolition.

Again, as to the middle passage, the evil is radical there also; the merchant’s profit depends upon the number that can be crowded together, and upon the shortness of their allowance. Astringents, escharotics, and all the other arts of making them up for sale, are of the very essence of the trade; these arts will be concealed both from the purchaser and the legislature. They are necessary to the owner’s profit, and they will be practiced. Again, chains and arbitrary treatment must be used in transporting them; our seamen must be taught to play the tyrant, and that depravation of manners among them (which some very judicious persons have treated of as the very worst part of the business) cannot be hindered, while the trade itself continues.

As to the slave merchants, they have already told you that if two slaves to a ton are not permitted, the trade cannot continue; so that the objections are done away by themselves on this quarter; and in the West Indies, I have shown that the abolition is the only possible stimulus whereby a regard to population, and consequently to the happiness of the negroes, can be effectually excited in those islands.

I trust, therefore, I have shown that upon every ground the total abolition ought to take place.

I have urged many things which are not my own leading motives for proposing it, since I have wished to show every description of gentlemen, and particularly the West India planters, who deserve every attention, that the abolition is politic upon their own principles also.

Policy, however, sir, is not my principle, and I am not ashamed to say it. There is a principle above everything that is political; and when I reflect on the command which says, “Thou shalt do no murder,” believing the authority to be divine, how can I dare to set up any reasonings of my own against it? And, sir, when we think of eternity, and of the future consequences of all human conduct, what is there in this life that should make any man contradict the dictates of his conscience, the principles of justice, the laws of religion, and of God.

Sir, the nature and all the circumstances of this trade are now laid open to us; we can no longer plead ignorance, we cannot evade it, it is now an object placed before us, we cannot pass it. We may spurn it, we may kick it out of our way, but we cannot turn aside so as to avoid seeing it; for it is brought now so directly before our eyes that this House must decide, and must justify to all the world, and to their own consciences, the rectitude of the grounds and principles of their decision.

A society has been established for the abolition of this trade, in which dissenters, Quakers, churchmen, in which the most conscientious of all persuasions have all united, and made a common cause in this great question.

Let not Parliament be the only body that is insensible to the principles of national justice.

Let us make a reparation to Africa, so far as we can, by establishing a trade upon true commercial principles, and we shall soon find the rectitude of our conduct rewarded by the benefits of a regular and a growing commerce.

I shall now move to several Resolutions upon which I do not ask the House to decide tonight, but shall consider the debate as adjourned to any day next week that may be thought most convenient, viz.

- That the number of slaves annually carried from the coast of Africa, in British vessels, is supposed to be about 38,000. That the number annually carried to the British West-India islands has on an average of four years, to the year 1787 inclusive, amounted to about 22,500. That the number annually retained in the said islands, as far as appears by the Custom House accounts, has amounted, on the same average, to about 17,500.

- That much the greater number of the negroes, carried away by European vessels, are brought from the interior parts of the continent of Africa, and many of them from a very great distance. That no precise information appears to have been obtained of the manner in which these persons have been made slaves. But that from the accounts, as far as any have been procured on this subject, with respect to the slaves brought from the interior parts of Africa, and from the information which has been received respecting the countries nearer to the coast, the slaves may in general be classed under some of the following descriptions:

1st, Prisoners taken in war.

2nd, Free persons sold for debt, or on account of real or imputed crimes, particularly adultery and witchcraft, in which cases they are frequently sold with their whole families, and sometimes for the profit of those by whom they are condemned.

3rd, Domestic slaves sold for the profit of their masters, in some places at the will of the masters, and in some places on being condemned for real or imputed crimes.

4th, Persons made slaves by various acts of oppression, violence, or fraud, committed either by the princes and chiefs of those countries on their subjects, or by private individuals on each other, or lastly by Europeans engaged in this traffic.

- That the trade carried on by European nations on the coast of Africa, for the purchase of slaves, has necessarily a tendency to occasion frequent and cruel wars among the natives, to produce unjust convictions and punishments for pretended or aggravated crimes, to encourage acts of oppression, violence, and fraud, and to obstruct the natural course of civilization and improvements in those countries.

- That the continent of Africa, in its present state, furnishes several valuable articles of commerce highly important to the trade and manufactures of this kingdom, and which are in a great measure peculiar to that quarter of the globe; and that the soil and climate have been found, by experience, well adapted to the production of other articles, with which we are now either wholly, or in great part, supplied by foreign nations. That an extensive commerce with Africa in these commodities, might probably be substituted in the place of that which is now carried on in slaves, so as at least to afford a return for the same quantity of goods as has annually been carried thither in British vessels. And lastly, that such a commerce might reasonably be expected to increase in proportion to the progress of civilization and improvement on that continent.

- That the slave trade has been found, by experience, to be peculiarly injurious and destructive to the British seamen who have been employed therein; and that the mortality among them has been much greater than in His Majesty’s ships stationed on the coast of Africa, or than has been usual in British vessels employed in any other trade.

- That the mode of transporting the slaves from Africa to the West Indies necessarily exposes them to many and grievous sufferings, for which no regulation can provide an adequate remedy; and that, in consequence thereof a large proportion of them has annually perished during the voyage.

- That a large proportion of the slaves so transported has also perished in the harbours in the West Indies previous to their being sold. That this loss is stated by the assembly of the island of Jamaica at about four and a half per cent of the number imported; and is, by medical persons of experience in that island, ascribed in great measure to diseases contracted during the voyage and to the mode of treatment on board the ships by which those diseases have been suppressed for a time in order to render the slaves fit for immediate sale.

- That the loss of newly imported negroes within the first three years of their importation bears a large proportion to the whole number imported.

- That the natural increase of population among the slaves in the islands appear to have been impeded principally by the following causes.

1st, The inequality of the number of the sexes in the importations from Africa.

2nd, The general dissoluteness of manners among the slaves, and the want of proper regulations for the encouragement of marriages and of rearing children.

3rd, Particular diseases which are prevalent among them and which are in some instances attributed to too severe labour or rigorous treatment and in others to insufficient or improper food.

4th, Those diseases which affect a large proportion of negro children in their infancy, and those to which the negroes newly imported from Africa have been found to be particularly liable.

- That the whole number of slaves in the island of Jamaica in 1768 was about 167,000. That the number in 1774 was stated by Governor Keith about 193,000. And that the number in December 1787 as stated by Lieut. Governor Clarke was about 256,000. That by comparing these numbers with the numbers imported into and retained in the island, in the several years from 1768 to 1774 inclusive, as appearing from the accounts delivered to the committee of trade by Mr. Fuller; and in the several years from 1775 inclusive, to 1787 also inclusive, as appearing by the accounts delivered in by the inspector general; and allowing for a loss of about one twenty-second part by deaths on ship board after entry, as stated in the report of the assembly of the said island of Jamaica, it appears, that the annual excess of deaths above births in the island in the whole period of nineteen years has been in the proportion of about seven eights per cent, computing on the medium number of slaves in the island during that period. That in the first six years of the said nineteen, the excess of deaths was in the proportion of rather more than one on every hundred on the medium number. That in the last thirteen years of the said nineteen, the excess of deaths was in the proportion of about three-fifths on every hundred on the medium number; and that a number of slaves, amounting to 15,000, is stated by the report of the island of Jamaica to have perished, during the latter period, in consequence of repeated hurricanes, and of the want of foreign supplies of provisions.

- That the whole number of slaves in the island of Barbados was, in the year 1764, according to the account given in to the committee of trade by Mr. Braithwaite 70,706. That in 1774, the number was, by the same account 74,874. In 1780, by ditto 68,270. In 1781, after the hurricane, according to the same account 63,248. In 1786, by ditto 62,115. That by comparing these numbers with the number imported into this island, according to the same account (not allowing for any re-exportation), the annual excess of deaths above births, in the ten years from 1764 to 1774, was in the proportion of about five on every hundred, computing on the medium number of slaves in the island during that period. That in the seven years from 1774 to 1780, both inclusive, the excess of deaths was in the proportion of about one and one-third on every hundred, on the medium number. That between the year 1780 and 1781, there appears to have been a decrease in the number of slaves of about 5,000. That in the six years from 1781 to 1786, both inclusive, the excess of deaths was in the proportion of rather less than seven-eighths in every hundred, on the medium number. And that in the four years from 1783 to 1786, both inclusive, the excess of deaths was in the proportion of rather less than one-third in every hundred on the medium number. And that during the whole period there is no doubt that somewhere exported in the first part of this period than in the last.

- That the accounts from the Leeward islands and from Dominica, Grenada, and St. Vincent’s, do not furnish sufficient grounds for comparing the state of population in the said islands at different periods, with the number of slaves which have been, from time to time, imported into the said islands, and exported from there. But that from the evidence which has been received respecting the present state of these islands, as well as of Jamaica and Barbados, and from a consideration of the means of obviating the causes which have hitherto operated to impede the natural increase of the slaves, and of lessening the demand of manual labour, without diminishing the profit of the planter, it appears that no considerable or permanent inconvenience would result from discontinuing the further importation of African slaves.

This text can be found in The Parliamentary History of England from the Earliest Times to 1803 Vol 28 comprising the period from the 8th May 1989 to the 15th March 1791 pp41-67. A facsimile of this volume can be found here: http://books.google.co.uk/books?id=YLQ_AAAAYAAJ&printsec=frontcover#v=onepage&q&f=false