23 July 1983

An audience with Joseph Nathaniel Hibbert, Rastafari patriarch

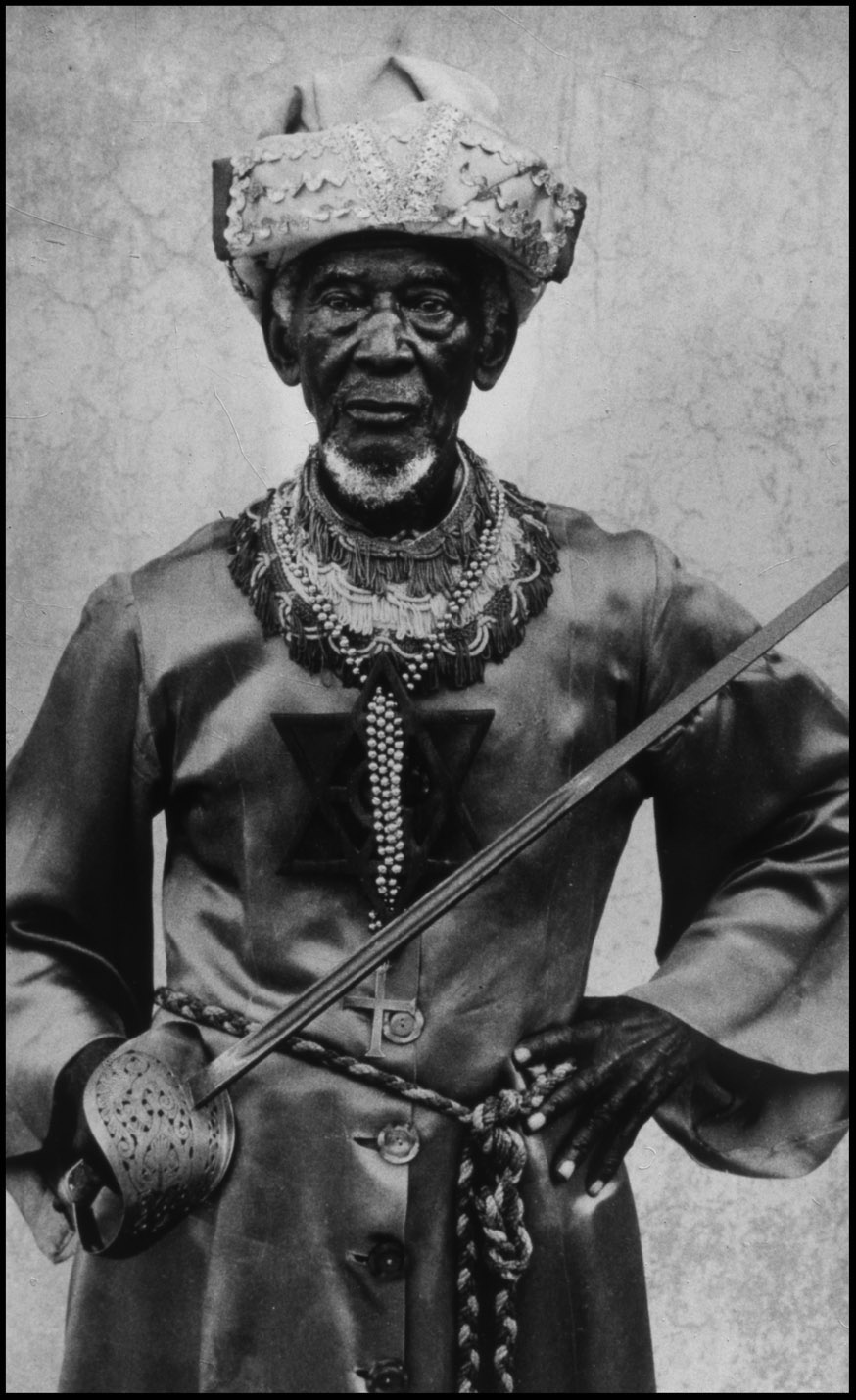

Joseph Nathaniel Hibbert in his Masonic ceremonial robes, Bulls Bay, Jamaica 1983. ©Derek Bishton

THIS IS an account of the interview I conducted with Father Joseph Hibbert, one of the first people to proclaim the divinity of Haile Selassie and a key figure in the early development of Rastafari in Jamaica in the 1930s.

I drove to his house in Bull Bay, just outside Kingston, with Speedy McPherson (the toaster from Jungleman Sound who was in Jamaica on holiday) and Sister Peaches, a young Rasta woman who had been assigned by elders from the Ras Tafari International Theocracy Assembly (RITA) being held at the UWI Mona Campus, to chaperone us. I asked her how she became a Rasta. “Well, it was through Bob Marley. When I heard the album Kaya I knew I must turn Rasta.” I expressed surprise. Kaya was the least well-received in Jamaica of all of Marley’s albums. By the time it was released, the local music scene had moved on. Bob sounded too soft. But this is what had appealed to Peaches. He was a man with vulnerabilities: he was human, but he was spiritual as well.

I asked her if everyone knew about Hibbert’s role in the founding of Rasta. “Oh yes,” she said. “Everyone knows about Father Hibbert.” In fact, at the conference Bongo Zack, a Rasta born in Jamaica but who had been living in Houston, Texas for the previous decade, spoke about seeing Father Hibbert in the early 1930s in Kingston. “I was a boy and the first thing I can remember was that Mr. Hibbert, every Sunday, he used to march right past the front of our house carrying a red, gold and green Ethiopian flag. You know those leather belts, the ones with a cup to hoist a flag pole, well Mr. Hibbert he used to wear this white robe, with a red, gold and green sash, and this belt to hoist the flag, and he would march right down to the corner and signal everyone that a meeting was going to take place that evening. As a boy I remember looking at this man. B’cau as I boy I wear pants, trouser, and I was looking at Mr. Hibbert who was the first man we did a see wear a robe . . . He was a strange man. . . who came from Costa Rica.” (1)

We arrived at Bulls Bay and approached the house with some trepidation (on my part at least). Father Hibbert, who was in his late 80s, emerged in shorts and vest, a wiry, dark-skinned man with grizzled white hair cut short. I explained why we had come: I wanted to record him saying what he used to preach standing on the street corners of Kingston in 1932. Would he be willing to do this? I said I would also like to take a photograph of him. He looked sternly at me and Speedy. He didn’t say anything and then turned and headed back into his house.

We sat around in his yard, not knowing what to expect. Nobody said anything, so I just assumed that events had moved into that other temporal and spiritual zone as they so often do in Jamaica, and sat down to wait. Then Father Hibbert emerged. He was dressed in a long, priestly, green satin gown, wearing a huge star of David and carrying a long sabre. On his head was something resembling a turban. His entire outfit was immaculate. The wait has probably been occasioned by the need for a serious session with the iron.

He started by telling me that, as a child, he had gone to Costa Rica, where he’d spent 20 years and three months “workin’, learnin’, and I return back to Jamaica 1931, month of October, the 12th, I reach back in Jamaica. I start proper to preach the Ethiopian Coptic Church in 1932.”

Father Hibbert’s sermon, densely populated with Old Testament references, was a condensed history of Ras Tafari’s lineage, more or less as set out in the Kebre Negast, which proved “Ras Tafari is the reincarnated body of Jesus Christ. So we have new creation now, new everything.”

The idea of reincarnated souls was central to Hibbert’s message. “The reincarnated Isiah became Elias who can now be proved to be – read Matthew 17 – John the Baptist. Today, Jesus Christ reincarnated back in the name of Ras Tafari. And John the Baptist came back in the name of Marcus Mosiah Garvey, another forerunner, mouthpiece and trumpeter.”

“When Moses hold the scroll of Joseph, he took that and lead the children out of Egypt to set us free. Well, Haile Selassie have led an army of 80,000 men and fought in an aircraft for seven months to set all the children free, and to set Africa free.”

And then he burst into song, and to the tune of John Brown’s Body bellowed out:

“Haile Selassie and his 80,000 men

Marching on the battlefield of Ethiopia lands

Seeing how the European is leaving our land

Ethiopia shout for joy

Glory, glory Haile Selassie

Glory, glory Haile Selassie

Glory, glory Haile Selassie

Glory, glory Haile Selassie

Ethiopians shout for joy.”

Then he fixed me with his small, intense eyes, as he must have fixed the crowds that gathered on the street corners of Kingston in the 1930s, to emphasise that his message was ultimately one of peace, a vision of a world where people could go to their bed at night with their doors left unlocked, safe in the knowledge “that Emperor Haile Selassie, creator of Israel, the holy man of Israel, the king of men, bring the new bible, a new earth and a new creation now.” He placed great emphasis on the words “new creation now.”

Then he drew himself to attention, inclined his head towards me and indicated I could take a photograph. The heat of the midday sun was intense and the light quite blinding. I asked him if he would move into the shade by the wall of the house, which he did. I fumbled with the settings on my camera, shot off half a dozen frames and he said: “Thank you, good morning,” and went back into his house as swiftly as he had appeared.

The Report on the Rastafari Movement (2) says of Father Hibbert: “Mr. Hibbert was born in Jamaica in 1894, but went with his adopted father to Costa Rica in 1911, returning to Jamaica in 1931. In Costa Rica Mr. Hibbert had leased 28 acres, which he put in bananas. In 1924 he had joined the Ancient Mystic Order of Ethiopia, a Masonic society the constitution of which was revised in 1888, and which became incorporated in 1928 in Panama. Mr. Hibbert became a Master Mason of this Order, and, returning to Jamaica, began to preach Haile Selassie as the King of Kings, the returned Messiah and the Redeemer of Israel. This was at Benoah District, St. Andrew, from whence he moved to Kingston to find Howell already preaching Ras Tafari as God at the Redemption Market.”

After a while, Father Hibbert reappeared, back in his shorts and vest. He asked me if I would find and send to him two publications – The National Geographic edition of June 1931 which contained coverage of Haile Selassie’s coronation and the edition of The Daily Mirror from November 1930 covering the same event. Both had been important documents at the time because they showed how the world had gone to bow down before the Emperor’s throne, he said. Unfortunately, over time, his copies had been lost. I promised to look out for them (I was unable to find a copy of the The Daily Mirror but I did get hold of a copy of the National Geographic which I sent to him).

Several months later, back in England, I discovered that the Ancient Mystic Order of Ethiopia was a fraternal order derived from Prince Hall Freemasonry. Prince Hall was a free black living in Boston in the latter half of the 18th century. He and a number of other free African Americans were attracted to Freemasonry because of the founding principles of liberty and equality, and because it offered an environment of secrecy which could not be easily breached. In this way, Prince Hall and his followers developed what historian James Sidbury described a “a fundamentally new ‘African’ movement on a pre-existing institutional foundation. Within that movement they asserted emotional, mythical and genealogical links to the continent of Africa and its peoples.(3)

Inevitably, this brought Prince Hall Freemasons into close association with the Ethiopian Church which is one of the few pre-colonial era Christian churches of sub-Saharan Africa. This in turn introduced members to the Coptic belief in the one single unified nature of Christ – that is the belief that a complete, natural union of the divine and human natures into one is self-evident in order to accomplish the divine salvation of humankind. This, of course, finds expression in the Rasta formulation of I and I – which stresses the idea that God dwells within everyone.

What also becomes clear from father Hibbert’s story is how important the movement around the Caribbean of black workers from North America and islands such as Jamaica was to the development of a diasporic African consciousness in the early part of the twentieth century. Marcus Garvey visited Costa Rica in 1910 where he published a small newspaper and thousands of Caribbean and North American workers were involved in building the Panama Canal from 1903 to 1914.

More recently, while I was preparing this blogpost, I re-read the transcript of Father Hibbert’s speech and I realised that one of the key messages was contained in his ideas about reincarnation. I am reminded of the lines from Bunny Wailer’s song Reincarnated Souls: “We are reincarnated souls from that time”. This was Hibbert’s key message to the downtrodden and dispossessed: Rastafari are divine people with a divine lineage.

(1) See http://rastaites.com/elders-i-stimony-1983-rita-nathaniel-hibbert/ (accessed 1 July 2019)

(2) M.G. Smith, Roy Augier and Rex Nettleford Report on the Rastafari Movement in Kingston, Jamaica, University of the West Indies (Kingston), 1960. p.6

(3) James Sidbury Becoming African in America : Race and Nation in the Early Black Atlantic. Oxford University Press. 2007. p. 73