05 June 1978

Talking Blues: the Black community speaks about its relationship with the police

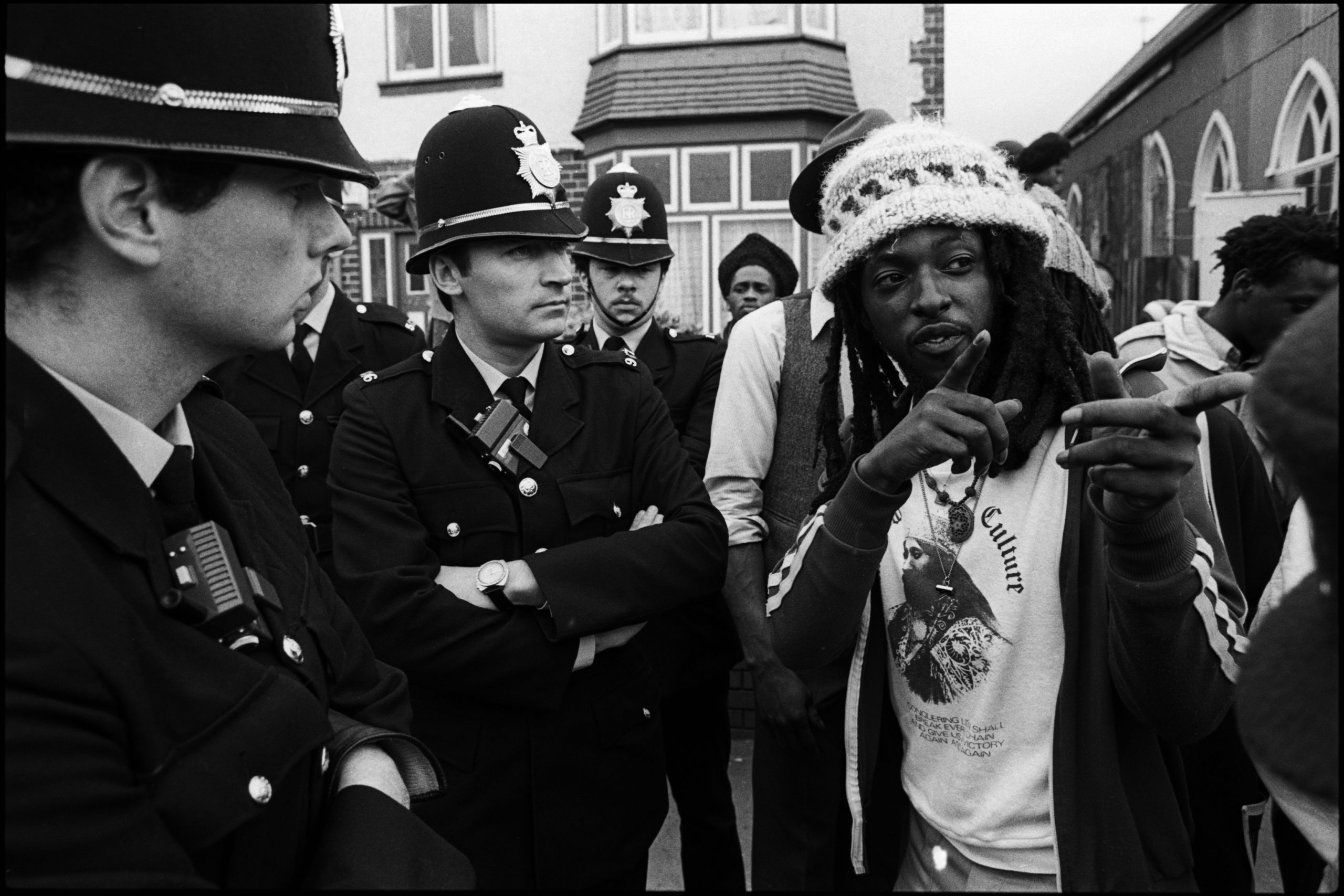

A young Rastaman explains to police why he and others are protesting outside a church in Aston photo: ©derek bishton

THE moral panic that followed the publication of The Shades of Grey report on policing in Handsworth and its central characterisation of the area as one terrorised by a gang of 200 criminal Dreadlocks provoked a powerful response from the black community. Within a few months the Affor community agency (1) had published Talking Blues, a 48-page collection of interviews with young black people, parents and church ministers that portrayed an altogether different reality – one of constant harassment, discrimination and racist behaviour on the part of the police.

The report revealed that almost all the young people interviewed were living in constant fear of being stopped and questioned by the police. “Our aim is not to knock the police,” wrote Clare Short in her introduction. “But the extent and depth of the feeling of injustice expressed in the interviews reflects a serious problem. And whilst it would be a serious mistake to blame the police for all that is wrong, it would be very foolish indeed not to accept that there is an urgent need for improvement in police attitudes and behaviour.”

This sentiment stood in stark contrast to the Shades of Grey report which had basically exonerated the police and traded on the racist trope that black people were much more disposed towards violence and criminality. The cruel irony of this position was exposed when crime statistics for Handsworth – one of the main areas of settlement for people from the Caribbean – showed that it had one of the lowest levels of recorded crime in the West Midlands and was the only sub-division (of 12) to experience a fall in 1977.

The commissioning and execution of the Talking Blues report was a massive community effort. Clare Short had been involved in discussions with senior police officers in 1976 about tensions between young black people and the police. This led to the commissioning of the Shades of Grey report, but Short was wary of the choice of author, John Brown, because of his close association with the police. Concerned that his report would turn out to be a whitewash, she began to mobilise members of the black community to produce their own report.

A key figure in this was bus driver Carlton Green, a familiar face in the area who, using only a basic Sony cassette recorder, starting visiting local pubs, clubs and houses where youngsters congregated, just asking people to “sound off” about their experiences. Carlton collected scores of interviews that were supplemented by others given by people who visited the Affor offices, including local priests and parents. There was no pretence that this was a scientific survey, but as Short observed: “The interviews with Church Ministers involved in youth work with young West Indians would, we thought, be of interest because they came from an unimpeachable source. They are not as forceful, eloquent and impatient as the words of the young blacks themselves but they do support the thesis that something is deeply wrong.”

I became involved in this project when Clare Short invited me and Brian Homer to help with editing the transcripts of the tapes which Short’s assistants Marcia Stewart and Cina Corcoran had diligently prepared. It was a daunting assignment.

It took me the best part of two weeks just to read through the transcripts. The scale of bad feeling and injustice was overwhelming. I knew things were on a knife edge in Handsworth: you couldn’t live there and not be aware that there was a real tension between young black kids and the police, but the scale of the resentment and anger revealed in these interviews was shocking.

Some of the interviews ran to several thousand words as interviewees poured out their frustrations and a litany of complaints about being stopped, searched, arrested, beaten up and charged with what they considered to be fabricated charges. One young man recalled that he was stopped as he walked along the street and charged with public indecency. The ‘indecency’ amounted to having a belt too big for his waist size so that one end dangled down between his legs.

His protests about the absurdity of this charge resulted in a further charge of resisting arrest. In this way, almost an entire generation of young black people were, in the space of a few years, criminalised for what were trivial or fabricated charges.

Inevitably, some of these street confrontations ended up in a struggle: if a policeman was even slightly injured, retribution in Thornhill Road police station was usually swift and brutal. Brian, one of those interviewed by Carlton Green, recalled that following an altercation in the street where he had been accused of stealing a tape recorder he was carrying, he was arrested along with two friends and thrown in a cell. “Five of dem come in and dem start beat me. Dem all go fe wet towel and take off all me clothes and start lick me with wet towel and kick and thump me till all me face swell. And dem charge me with disorderly conduct and wouldn’t let me out of the police station. Dem keep me there two days because dem didn’t want anyone to see the state I was in, because the whole of us just bruise up. Even after I get bail after the two days we had swellings and bruises and we went to the doctor and the doctor took pictures and write out report and we bring it to court. But we didn’t get nothing out of it because the judge believe the police. That convince me of the situation with white people against black people that dem is our oppressor, that dem people hate we. Dem regard us as lower than dem animals . . .”

In total, Carlton Green and the Affor researchers interviewed 34 young black men and women, including Rastafarians, members of church youth clubs and students, including one studying at Birmingham University. In addition opinions were sought from nine West Indian parents and six church ministers actively involved in youth work in the area. More than a third of the people interviewed had experienced police harassment or brutality themselves and nearly every other interviewee recounted incidents relating to close friends or family members.

After reading and studying the transcripts for a couple of weeks, several issues emerged as recurrent themes – such as the belief that white society looked down on black people and regarded them as inferior, the impact of high unemployment rates, the lack of respect shown by police, and the widespread fear of the police, for example. In order to make the final edit of these transcripts as coherent as possible, I suggested that we extract the most powerful expressions of these various issues to create a narrative that reflected the themes we had identified.

One of the recurrent complaints from interviewees was that the police were completely ignorant of the history and culture of African Caribbean people and that this created many misunderstandings and a lack of empathy. Since everyone involved in producing Talking Blues was hoping that this report would be circulated amongst local police, we agreed it would make sense to include a Background section that highlighted the importance of understanding how slavery, colonialism and poverty had a direct bearing on West Indian life today in the UK. This was provided by Danzie Stewart, a black social worker who was brought up in Handsworth.

Brian and I then went on to design the booklet, using photographs we had taken in the area with cover artwork commissioned from Handsworth-based illustrator Martin Lealan. As with all the work we produced at Sidelines, the aim was to create a publication with a strong visual impact. It took several months during the early part of 1978 to produce the final artwork. In those pre-digital, analogue days we had to mark up the copy and send it to be typeset into galley form. These were then sliced up to fit on layout boards, with headings made using Letraset – transfer lettering rubbed off a backing sheet by hand. By the beginning of May we were ready to go to print. Talking Blues was eventually published at the beginning of June.

I prepared a press release and Brian and I compiled a list of media organisations, including local and national newspapers, local TV and radio stations, and other campaign groups such as Race Today and the National Council for Civil Liberties which staff at Affor contacted and sent copies of the report to. Other copies were circulated to West Midlands police units, MPs and councillors and Social Services and Probation officers. Copies also went on sale in alternative bookshops around the UK and many copies were supplied to libraries.

Talking Blues received extensive coverage in The Observer, The Times, The Guardian, The Birmingham Post and the Jamaican Weekly Gleaner.

It was, I think, a landmark grassroots intervention in the fight against institutionalised racism.

See: 08 December 1977 Shades of Grey – a report on Police-West Indian relations in Handsworth

(1) Affor (All Faiths for One Race) was a community advice and campaigning agency based on Lozells Road. It had been set up initially to lobby against the proposed South African cricket tour in 1970, with support from a wide range of religious leaders in Birmingham. It evolved to become a powerful voice in anti-racist struggles, producing many booklets and newsletters – most of which were produced by the Sidelines agency (Brian Homer, Derek Bishton and John Reardon).