RETURN TO ABOUT SUMMARY PAGE.

About Derek Bishton

#BIRMINGHAM #CAMBRIDGE #FITZWILLIAMCOLLEGE #BROADSHEET #GRAPEVINE #SIDELINES #TEN8 #HANDPRINT #THEDAILYTELEGRAPH #ELECTRONICTELEGRAPH

I was born in Birmingham in 1948. My father, who had served a seven-year apprenticeship as a letterpress printer before the onset of WW II, found it difficult to settle after the war and we moved about a lot before he finally settled back in Birmingham in the mid-1950s.

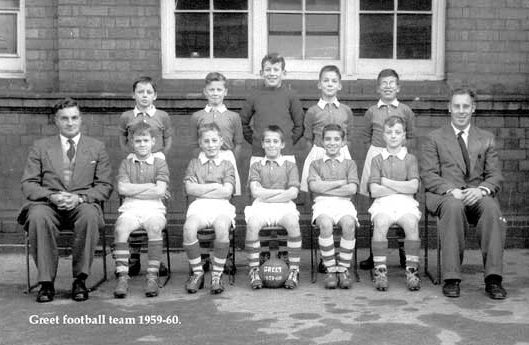

I went to Greet Primary School where, because I was the tallest, I was selected as goalkeeper in the school football team.

From Greet I went on to Kings Heath Boys’ Technical, a new school where I was part of the initial intake. Being a senior boy from day one had some unexpected benefits, which included intensive academic and pastoral support. To the great surprise of my parents and most of my family – none of whom had advanced beyond the age of 14 in formal education – I was offered a place at Fitzwilliam College, Cambridge in 1967, where I read English.

Cambridge was a challenging place for a working class boy to negotiate 50 years ago (it’s probably not much easier now) but I soon discovered that journalism, writing and publishing were key tools in the struggle to speak truth to power and privilege.

I edited the weekly arts and cultural review Broadsheet in my final year (along with my great friend Nick Clark who later became a well-known voice on BBC Radio4 and who sadly died in 2006) and was offered a place on the Thomson newspapers training scheme when I graduated. I spent two years in Newcastle working on The Evening Chronicle and then moved to Birmingham where I became deputy features editor of The Birmingham Post.

During this time I began helping out with editing and designing Grapevine, Birmingham’s original alternative newspaper. It was there I met Brian Homer, the magazine’s managing editor and when my first marriage floundered I decided to leave mainstream journalism and work in the community to try to put some of my political beliefs into practice by helping people trying to combat racism and social inequality.

In 1977, I joined with Homer to establish Sidelines, a community design and photography resource, where we were joined by photographer John Reardon in 1978. This collective – which attracted many other artists, activists and media workers – became a crucial focal point for alternative journalism, design, photography and work with inner city political groups and organisations from 1977 – 1985.

Sidelines was based in Grove Lane, Handsworth and worked for virtually every voluntary organisation in the inner city – producing hundreds of reports, magazines, books, photographs and posters for groups involved in social justice, anti-racism, unemployment, housing, police-black relations and social issues.

Key publications included Movement of Jah People (1977) the first book published in the UK addressing the growth and beliefs of the Rasta movement; Talking Blues (1978) nominated for the Martin Luther King Jnr Peace Prize, which documented the crisis in relations between young black people and the police; the Saltley Community Development Project series of final reports about the causes of inner city deprivation, poverty and unemployment; and The Sweatshop Report (1981) which documented and analysed the reasons behind the growth of sweated labour in post-industrial Britain.

Along with Homer and Reardon I was also a key mover in establishing the photographic journal Ten.8, which began in 1978 with a brief to establish links between photographers in the West Midlands region, but quickly attracted a national and then an international audience. The principal focus of the journal, the relationship between power and representation, was inspired and informed by the day-to-day experiences of working in the inner city.

Over the following 14 years Ten.8 published 38 editions containing work by most of the leading photographers, critics and cultural theorists of the period including Professor Stuart Hall, Allan Sekula, Kobena Mercer, Pratibha Parmar, Rotimi Fani-Kayode, Jo Spence, Paul Gilroy, Sunil Gupta, Lorna Simpson, Carrie Mae Weams, Sonia Boyce, David A Bailey, Roy DeCarava, Martha Rosler, Jan Zita Grover, Maud Sulter, Jean Moutoussamy-Ashe, Abbas, Victor Burgin, Martin Parr, and John Tagg (amongst many others).

I was a member of the editorial board from its inception until it ceased publication and was responsible for encouraging debates around the cultural politics of race and representation, post-colonial theory and the critical questions of hybridity, marginalisation and identity that emerged in the UK during the 1980s.

Individually and collectively, Sidelines produced a huge body of photographic work. Our first project, the Handsworth Self Portrait in 1978 (see Instagram page /handsworthselfportrait), was created specifically to allow people who had been stereotyped and objectified to put themselves, literally, in the frame. The images, made on the street outside the Sidelines office in Handsworth over the summer of 1979, were widely exhibited, inspired many similar projects, and now form part of the Autograph ABP archive in London. In 2019, I curated a 40th anniversary exhibition of images from the project which included 44 vintage prints made by John Reardon and more than 200 others images which had never been seen before in public. The exhibition was held at Mac, Birmingham from March 23 – June 2.

In 1981, as a direct result of the work I had undertaken with Rastas following the publication of Movement of Jah People, I went to Shashemane, the town in Ethiopia where Emperor Haile Selassie had set aside a parcel of land for people from the African diaspora who wanted to return ‘home’. I spent six weeks living with and amongst the small community of pioneer settlers, mostly Rastafari from Jamaica. They included Papa Noel Dyer who had arrived in Shashemane in 1965 having walked all the way from England, and members of various Rasta organisations including the Twelve Tribes and the Ethiopian World Federation.

My report and photographs from this visit were subsequently published in the book Black Heart Man (Chatto & Windus 1986) and helped stimulate much more interest in the Promised Land of Shashemane.

I first visited Jamaica later the same year and have been returning on a regular basis ever since. My photograph of Joseph Nathaniel Hibbert, one of the patriarchs of the Rasta movement, was taken on a visit in 1983 and is now part of the National Museum of Jamaica collection.

My documentary work in Birmingham, much of it made in response to requests from community groups, was collected alongside work by John Reardon in the book Home Front (Jonathan Cape 1984) with an introduction by Salman Rushdie.

In 1983 I began working with my wife Merrise Crooks who had established Handprint, a voluntary agency supported by Albsu (Adult Literacy & Basic Skills Unit) to create educational resources specifically aimed at young black people who had left school with low literacy levels.

Handprint published two sets of basic readers, a magazine for young women and a multimedia tape-slide about Rastafari and repatriation for which I provided photographs and the commentary. From 1987 on, Handprint was self-financing and undertook design and publishing work for other organisations including Save The Children (Scotland), The Black Dance Trust, Birmingham Women’s Festival, Black Voices group and many others.

From 1985 to 1987 I was Director of Triangle Media Centre Photography Gallery in Birmingham where I initiated a programme based around commissioning local photographers, and supporting their development through workshops, training and an MSC scheme. In addition, I brought important work made by national and international artists such as Martin Parr, Armet Francis and David A Bailey to the gallery.

I was an early adopter of Apple computers, which I used to develop desktop publishing for both Ten.8 and Handprint. I saw the potential of digital technology and the development of the internet as tools that could provide previously marginalised communities with ways to reach much wider audiences.

The ‘Black Monday’ financial crash of 1987 decimated the voluntary sector in the UK as grant aid was withdrawn from thousands of organisation and groups. This led to the eventual closure of Handprint and Ten.8.

After struggling – and failing – to keep these projects viable, I was offered a short-term contract at The Daily Telegraph in 1993. I spent a year as a commissioning editor on the Telegraph Magazine, and then joined the launch team of the UK’s first internet newspaper, electronic telegraph – now telegraph.co.uk – which came online in November 1994. I became editor in 1996 and under my tenure electronic telegraph won numerous awards, creating a template for an interactive news service that The Guardian and BBC News were to follow. I received the London Press Club New Media Award in 2003.

In 2004 I became Telegraph Group Consultant Editor, a role with a wide-ranging portfolio. It included leading a team overseeing the editorial transition to a new digital production system for the newspaper titles, and the integration of online and print editorial departments. In 2010 I won a UK Press Award for Best Special Supplement for my work with Himesh Patel as part of the newspaper’s exposé of the MPs’ expenses scandal.

I now work as a freelance journalist and social media consultant alongside developing my own projects such as An Infinity of Traces.