05 February 1793

Bligh and the breadfruit: the role of botany in Empire

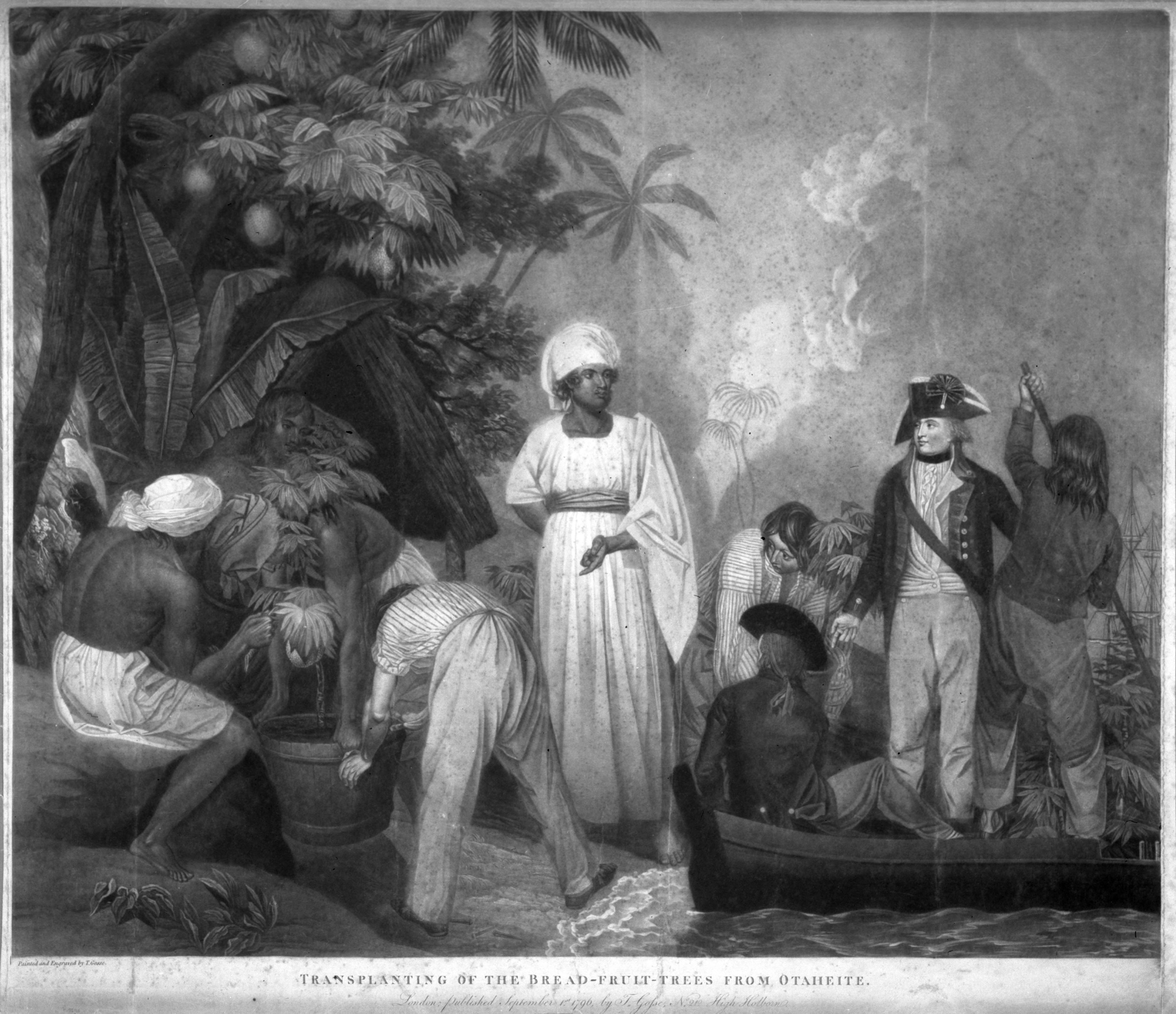

Transplanting the breadfruit trees from Otaheite, Tahiti by Thomas Gosse

IN MY household, nothing speaks more powerfully to nostalgic memories of Jamaica than a freshly roasted breadfruit, its charred exterior peeled away to reveal the firm, sweet, yellow flesh. Eaten in segments doused in black pepper and melted butter, it is the food of the Gods. It’s almost as good the following day, refried, for breakfast. But breadfruit is not native to the Caribbean: like other exotic fruits which have become synonymous with Jamaica such as coconuts and mangos, they arrived as part of the imperial arms race around food security that accompanied the slave trade. When William Bligh, who survived one of the most infamous mutinies in British naval history on his first attempt to transport examples of this super food to the Caribbean, finally landed in Jamaica in 1793 on his second voyage from Tahiti with his cargo of breadfruit saplings, he was fulfilling a key role in the expansion of the British empire.

The breadfruit tree had been exciting interest amongst planters and naturalists since the rise to prominence of Sir Joseph Banks, a botanist who had sailed with Captain Cook on his first voyage (1768-1771) visiting Brazil, Tahiti (where he had first encountered breadfruit), New Zealand and Australia. Banks subsequently became an adviser to George III and was a powerful and influential advocate for the international exchange of resources, in the process making Kew one of the pre-eminent botanical gardens in the world.

The West Indian lobby had long offered large rewards to any captain who could bring breadfruits to the Caribbean plantations but the desire to find alternatives to maize and plantain as staples for the enslaved population intensified between 1780 (the year of the ‘Great Storm’) and 1786 when Jamaica suffered from a series of devastating hurricanes followed by long periods of drought that destroyed most of the crops. Slave provision grounds were hard hit and there were major food shortages. In addition, the American War of Independence (1775-1783) had disrupted food supplies to the Caribbean. The islands relied heavily on food imports from North America but the onset of war stopped this trade. With food scarce, the enslaved population succumbed to disease and nutritional disorders. The Jamaica Assembly estimated in 1786 that more than 15,000 enslaved people had died as a result in the previous seven years.

When the offer of financial rewards failed to attract any takers, the planters successfully petitioned King George III and his advisor Sir Joseph Banks and he was instrumental in raising funds and selecting William Bligh, an experienced 33-year-old seaman who had sailed with Capt. Cook on his second voyage around the world from 1772-75, as commander of this expedition. Bligh with his first mate and good friend Fletcher Christian, set sail from Portsmouth, for Tahiti and Timor on the HMS Bounty a few days before Christmas, 1787. Their mission was to collect seedless breadfruit plants and deliver them to Jamaica.

This voyage famously ended with a mutiny led by Fletcher Christian and Blight was abandoned in a lifeboat with 18 loyal crew. With food sufficient for only a week, Bligh navigated through high seas and storms for 48 days, drawing on his memory of the few charts he had seen of the mostly uncharted waters. His completion of the 3,618-mile voyage to safety in Timor is still regarded as one of the most outstanding feats of seamanship and navigation ever conducted in a small boat.

As a token of its esteem and trust, the British Admiralty promoted the young Lieutenant Bligh to Captain — and, with the support of Banks, immediately packed him off on another two-year mission, back to Tahiti for the breadfruit. Two thousand one hundred and twenty-six breadfruit plants were carried from Tahiti, in pots and tubs stored both on deck and in the below-deck nursery. In spite of flies, salt spray and rationed water, 678 survived as far as the West Indies, being delivered first to St. Vincent and finally to Jamaica. And it was on 5 February 1793 that Capt. William Bligh, fulfilling at last his momentous commission, oversaw his first deposition of 66 breadfruit specimens from Tahiti, all “in the finest order,” in Bath Botanical Gardens.

The Jamaican village of Bath is home to one of the oldest botanical gardens in the world. It was established in 1779, its collection jump-started by the capture of a French ship coming from Mauritius laden with Indian mangos, cinnamon and other exotics that included the jackfruit and June plum – all of which have become common all over Jamaica. In the eighteenth century botanical collections had become a global enterprise, undertaken by colonial powers to establish plant collections for study and propagation. While most specimens gathered by British collectors were destined for the Royal Botanical Gardens at Kew, some went to satellite stations such as the one at Bath.

Bligh’s ship Providence had arrived at Port Royal, Kingston, to some fanfare, its “floating forest,” according to an officer of the ship, “eagerly visited by numbers of every rank and degree”— so much so that, as another officer complained, “the common Civility of going around the Ship with them and explaining the Plants became by its frequency rather troublesome.” Leaving Kingston, Bligh sailed for Port Morant. Here, the day after his arrival, with temperatures in the 70s and a fine breeze blowing, the HMS Providence had been emptied of its last 346 plants, which were carried six miles overland on the heads of bearers and deposited in a shady plot in the gardens.

Plants were also distributed to other parishes and Bligh was awarded 1500 guineas by the Jamaican Assembly. The breadfruit grew naturally on Jamaican soil, but it took many years before the enslaved population would attempt to eat the fruit they regarded as strange and which was tainted by its association with slavery. Reports from the late 19th century state that the fruit was not greatly favoured and was fed mostly to pigs.

However, perceptions have changed – and not just in my kitchen. Breadfruit is now seen as a key to food security in many parts of the world because it’s high in complex carbohydrates, protein, and micronutrients like iron and zinc. There are also non-nutritional advantages. The tree is low maintenance, sturdy and doesn’t require agrochemicals. And it’s fairly efficient. It yields a lot of food for the amount of space it takes up.