20 June 1837

Former slave James Williams’s autobiography exposes the evils of post-emancipation Jamaica

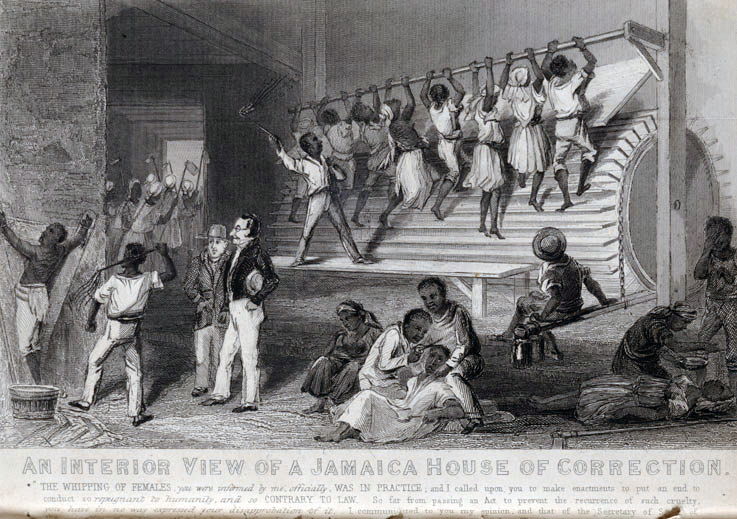

An interior view of a Jamaica house of correction from James Williams. A narrative of events since the 1st of August 1834. London, printed for the Central Emancipation Committee, 1838

JAMES WILLIAMS’s Narrative of Events – one of the very few autobiographical texts by a Caribbean who had experienced slavery – was a key text in the transatlantic campaign to fully abolish the lingering legacies of slavery in Britain’s Caribbean colonies.

Williams, an 18-year-old Jamaican ‘apprentice’, came to Britain in 1837 at the instigation of the abolitionist Joseph Sturge. His Narrative became one of the most powerful abolitionist tools for effecting the immediate end to the system of apprenticeship that had required newly-freed people to work for their former masters for between four and six years after the passing of the Slavery Abolition Act of 1833.

Williams describes the hard working conditions on plantations and the harsh treatment of apprentices unjustly incarcerated. He argues that apprenticeship actually worsened the conditions of Jamaican ex-slaves: former owners, no longer legally permitted to directly punish their workers, used the Jamaican legal system as a punitive lever against them.

Williams’s story documents the collaboration of local magistrates in this practice, whereby apprentices were routinely jailed and beaten for both real and imaginary infractions of the apprenticeship regulations.

James Williams lived on the Penshurst plantation of the Senior family in St. Ann’s Parish, Jamaica. The 1833 Act designated all enslaved people over the age of six as ‘apprentices’ who would be set free at the end of their term of service. Starting August 1, 1834, household slaves were apprenticed to a four-year term of service, and field slaves to a six-year term of service. Freed slaves and apprentices, however, were subject to work and living conditions that were virtually the same as those that had existed under slavery.

In January 1837, Williams, then an eighteen-year-old man with no wife or children, was introduced to a group of British anti-apprenticeship activists who were visiting Jamaica. One of them, Joseph Sturge, was a wealthy Quaker businessman who supplied the money for Williams to purchase his freedom. Sturge was impressed with Williams and the powerful way he told his story and arranged to take Williams to Britain and to publish his Narrative.

Williams worked with Dr. Archibald Leighton Palmer, a Scottish doctor he had met in Jamaica, to write the Narrative. It was published in June 1837 and quickly reprinted in multiple editions and in newspapers throughout Britain and Jamaica. Williams’s Narrative became iconic. His name and detailed accounts of the abuses suffered by apprentices became a common reference in published debates of the period. In September 1837, a Commission of Inquiry was opened regarding the abuses of apprentices in Browns Town, Jamaica. Over a period of three weeks, evidence was gathered from a large number of witnesses, including more than 120 apprentices. The evidence verified the Narrative’s truthfulness, and accounts of the testimonies were published in pamphlets with such titles as James Williams’s Narrative fully confirmed in the report of a Special Commission issued from the Colonial Office.

Williams’s Narrative does not provide details about his childhood, early life, or experiences outside the apprenticeship system. Instead, it is a record of the frequent punishments and abuses he experienced while apprenticed to the Senior family. The new law enacted by Parliament changed the relationship between slaveholders and slaves, not only setting an end-date to enslaved people’s terms of service, but also decreeing that punishments would be administered by magistrates, not slaveholders. However, this system did not alleviate the physical abuses slaves suffered, and Williams’s goal in writing his Narrative was to show that “Apprentices get a great deal more punishment now than they did when they was slaves; the master take spite, and do all he can to hurt them before the free come.”

The Foreword by Dr Thomas Price of Hackney, London dated June 20, 1837 of A Narrative of Events since the first of August, 1834, by James Williams, an apprenticed labourer in Jamaica states: “The following narrative of James Williams has been carefully taken down from his lips. It was deemed better to preserve his own peculiar style, rather than by any attempt at revision, to endanger the self-evident proof of fidelity, which his account bears. I have now before me a document, signed by two free negroes and six apprentices, all members of a Christian church in Jamaica, in which they affirm, that they have known the narrator from his infancy, and that he ‘is steady, sober, industrious, of good moral character, and that his word may be relied upon’.”

• Note: I have made extensive use of Diana Paton’s excellent introduction to A Narrative of Events since the First of August, 1834, by James Williams, an Apprenticed Labourer in Jamaica, published by Duke University Press, 2001 in compiling this Trace.

An excerpt from the Narrative

I AM about eighteen years old. I was a slave belonging to Mr. Senior and his sister, and was brought up at the place where they live, called Penshurst, in Saint Ann’s parish, in Jamaica. I have been very ill treated by Mr. Senior and the magistrates since the new law come in. Apprentices get a great deal more punishment now than they did when they was slaves; the master take spite, and do all he can to hurt them before the free come;–I have heard my master say, “Those English devils say we to be free, but if we is to free, he will pretty well weaken we, before the six and the four years done; we shall be no use to ourselves afterwards.”

Apprentices a great deal worse off for provision than before-time; magistrate take away their day, and give to the property; massa give we no salt allowance, and no allowance at Christmas; since the new law begin, he only give them two mackarel, –that was one time when them going out to job. When I was a slave, I never flogged – I sometimes was switched, but not badly; but since the new law begin, I have been flogged seven times, and put in the house of correction four times.

Soon after 1st August, massa tried to get me and many others punished; he brought us up before Dr. Palmer, but none of us been doing nothing wrong, and magistrate give we right. After that, Mr. Senior sent me with letter to Captain Connor, to get punished, but magistrate send me back – he would not punish me, till he try me; when I carry letter back to massa, he surprise to see me come back, he been expect Captain Connor would put me in workhouse. Capt. Connor did not come to Penshurst; he left the parish. Massa didn’t tell me what charge he have against me.

When Dr. Thompson come to the parish, him call one Thursday, and said he would come back next Thursday, and hold court Friday morning. He come Thursday afternoon, and get dinner, and sleep at Penshurst, and after breakfast, all we apprentices called up. Massa try eight of we, and Dr. Thompson flog every one; there was five man, and three boys: them flog the boys with switches, but the men flog with the Cat. One of the men was the old driver, Edward Lawrence; Massa say he did not make the people take in pimento crop clean; he is quite old – head quite white – haven’t got one black hair in it, but Dr. Thompson ordered him to be flogged; not one of the people been doing any thing wrong; all flog for trifling, foolish thing, just to please the massa.

When them try me, massa said, that one Friday, I was going all round the house with big stone in my hand, looking for him and his sister, to knock them down. I was mending stone wall round the house by massa’s order; I was only a half-grown boy that time. I told magistrate, I never do such thing, and offer to bring evidence about it; he refuse to hear me or my witness; would not let me speak; he sentence me to get 39 lashes; eight policemen was present, but magistrate make constable flog at first; them flog the old driver first and me next; my back all cut up and cover with blood, – I could not put on my shirt – but massa say, constable not flogging half hard enough, that my back not cut at all; – Then the magistrate make one of the police take the Cat to flog the other three men, and him flog most unmerciful. It was Henry James, Thomas Brown, and Adam Brown that the police flog.

Henry James was an old African; he had been put to watch large corn-piece – no fence round it – so the cattle got in and eat some of the corn – he couldn’t help it, but magistrate flog him for it. After the flogging, he got quite sick, and begin coughing blood; he went to the hot-house, but got no attention, them say him not sick. – He go to Capt. Dillon to complain about it; magistrate give him paper to carry to massa, to warn him to court on Thursday; that day them go to Brown’s Town, Capt. Dillon and a new magistrate, Mr. Rawlinson, was there. Capt. Dillon say that him don’t think that Henry James was sick; he told him to go back, and come next Thursday, and he would have doctor to examine him; the old man said he did not know whether he should live till Thursday; He walk away, but before he get out of the town, he drop down dead–all the place cover with blood that he puke up. He was quite well before the flogging, and always said it was the flogging bring on the sickness.

Same day Henry James dead, massa carry me and Adam Brown before magistrate; he said I did not turn out sheep till nine o’clock on Wednesday morning; I told magistrate the sheep was kept in to be dressed, and I was eating my breakfast before dressing them; but Capt. Dillon sentence me and Adam Brown to lock up in the dungeon at Knapdale for ten days and nights; place was cold and damp, and quite dark – a little bit of a cell, hardly big enough for me to lie full length; them give we pint of water and two little coco or plantain a day; – hardly able to stand up when we come out, we was so weak; massa and misses said we no punish half enough; massa order we straight to our work, and refuse to let we go get something to eat.