08 February 1816

Matthew Lewis on ‘the highest object of the brown females of Jamaica’

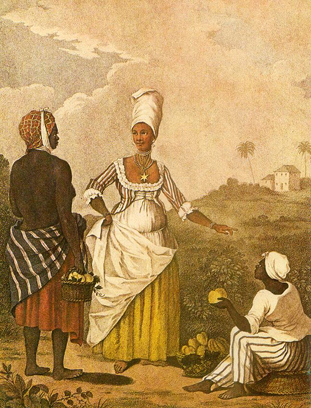

Barbados Mulatto Girl by Agostino Brunias (1764) (Public Domain)

DURING an overnight stop in Rio Bueno en route to his estate in Cornwall, Lewis falls into conversation with his landlady – “a very pretty brown girl.” She tells Lewis she is the wife of an English merchant in Kingston who has provided her with a house. Lewis comments: “This kind of establishment is the highest object of the brown females of Jamaica; they seldom marry men of their own colour, but lay themselves out to captivate some white person who takes them for mistresses, under the appellation of housekeepers.” Lewis ends his dairy entry with a patronising jingle about these ambitions. His observations about mulatto women clearly reflect prevailing beliefs about the sexual appetites of women of colour and they also underline the way in which European prejudices based on race, colour and caste had become internalised at every level of Jamaican society.

It was at Porto Bueno that Columbus is said to have made his first landing on the island. Rio Bueno is a small town with a fort, situated close to the sea. Here also we found a very good inn, kept by a Scotchman. The present landlady (her father being from home) was a very pretty brown girl, by name Eliza Thompson.

She told me that she was only residing with her parents during her husband’s absence; for she was (it seems) the soi-disant wife of an English merchant in Kingston, and had a house on Tachy’s Bridge. This kind of establishment is the highest object of the brown females of Jamaica; they seldom marry men of their own colour, but lay themselves out to captivate some white person who takes them for mistresses, under the appellation of housekeepers.

Soon after my arrival at Cornwall, I asked my attorney whether a clever-looking brown woman, who seemed to have great authority in the house, belonged to me? No; she was a free woman. Was she in my service, then? No; she was not in my service. I began to grow impatient. “But what does she do at Cornwall ? Of what use is she in the house?” “Why sir, as to use … of no great use, sir;” and then, after a pause, he added in a lower voice, “It is the custom, sir, in this country, for unmarried men to have housekeepers, and Nancy is mine.”

But he was unjust in saying that Nancy is of no use on the estate; for she is perpetually in the hospital, nurses the children, can bleed, and mix up medicines, and (as I am assured) she is of more service to the sick than all the doctors. These brown housekeepers generally attach themselves so sincerely to the interests of their protectors, and make themselves so useful, that they in common retain their situation; and their children (if slaves) are always honoured by their fellows with the title of “Miss”.

My mulatto housemaid is always called “Miss Polly,” by her fellow-servant Phillis. This kind of connection is considered by a brown girl in the same light as marriage. They will tell you, with an air of vanity, “I am Mr. Such-a-one’s Love!” and always speak of him as being her husband; and I am told, that, except on these terms, it is extremely difficult to obtain the favours of a woman of colour. To gain the situation of housekeeper to a white man, the mulatto girl “directs her aim;

This makes her happiness,

and this her fame.”

From Journal of a West Indian Proprietor Kept during a Residence in the Island of Jamaica by Matthew Lewis, Oxford University Press.