17 August 1983

Michael Smith: Jamaica’s greatest dub poet talks to Paul Bradshaw

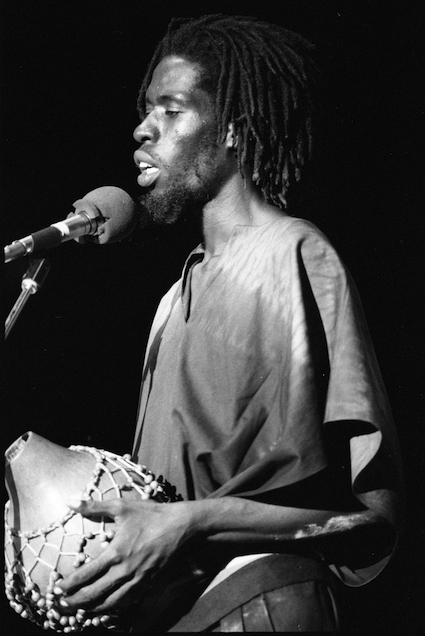

Mikey Smith performing at Reggae Sunsplash, Jamaica, July 1983 Photo ©Derek Bishton

“MIKEY SMITH’s brutal murder on 17 August, 1983 robbed Jamaica of one of its most visionary and talented poets. His album Mi Cyaan Believe It is a classic, and in my opinion, one of the greatest reggae-dub poetry albums ever made.

I met Mikey in Kingston, a few months before his death, at a Jamaica National Dance Theatre Company performance of Rex Nettleford’s reggae ballet and again a few weeks later when he performed at Reggae Sunsplash. He was due to tour in the UK later that year and we arranged to meet in London.

Sadly it was not to be. At a political meeting in Stony Hill, on the outskirts of Kingston, he had heckled a Jamaica Labour Party cabinet minister. Walking in the vicinity the following day, he was confronted by three party activists. According to Jamaica’s Daily Gleaner of August 19 he was “hit on the head by a stone thrown by one of three men who had attacked him… An argument between Smith and the men at about 11 o’clock led to his death.”

Michael Smith – known universally as Mikey – was born in Kingston on 14 September, 1954. Writing about Mikey, the poet and writer Mervyn Morris said: “He came from a working class background: his father was a mason, his mother a factory worker.

He began writing poems in the late 1960s. The first success he recalled was a poem provoked by a news item about Ian Smith, Prime Minister of Rhodesia (which had just declared itself independent of the United Kingdom). ‘One morning me did get up and just see Smith Seh No To Black Majority Rule, and me just write a poem.’ The audience responded warmly when he read the poem at a Community Centre in Golden Spring.”

Mikey became a student at the Jamaica School of Drama, where he developed the breath control and deep resonances of his baritone voice that were to become one of the defining features of his performance style. By the end of the 1970s he was performing before large crowds at political and cultural events.

Linton Kwesi Johnson, who was instrumental in setting up the recording of his album, gives the following outline of Mikey’s international success. “In 1978 Michael Smith represented Jamaica at the eleventh World Festival of Youth and Students in Cuba. That year saw the release of his first recording, a twelve-inch forty-five titled Word accompanied by Count Ossie’s Mystic Revelation of Rastafari drummers. In 1981 Mikey performed in Barbados during Carifesta (a Caribbean regional cultural festival), and was filmed by BBC Television performing Mi Cyaan Believe It for the documentary From Brixton to Barbados. In 1982 Mikey took London by storm with performances at the Camden Centre during the International Book Fair of Radical, Black and Third World Books and also at the Lambeth Town Hall in Brixton for Creation for Liberation.

“Whilst in Britain, Mikey recorded a reggae album which Island Records released under the title Mi Cyaan Believe It. The story did not end there: the BBC’s Anthony Wall made a television programme about Mikey for the flagship arts series Arena. Entitled Upon Westminster Bridge, the programme was broadcast on BBC2 that year.”

See https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/p00k1zlh

The journalist and broadcaster Paul Bradshaw interviewed Mikey Smith for NME in October 1982. Many thanks to Paul for his kind permission to reproduce his article here.

THE sounds of Count Ossie and The Mystic Revelation of Rastafari rise and fall on the slight breeze across the Red Hills valley where Michael Smith sits in the shade, nursing a Red Stripe. He is tall, slim ‘n’ dread, with a distinctive limp and a serious expression which breaks often into a broad grin and wicked laughter.

A dramatic and electrifying performer, Mikey has matured considerably since the release of his classic ‘Mi Cyaan Believe It’ in ’78. Now his Linton Kwesi Johnson produced LP is about to be released along with his first volume of poetry and a forthcoming BBC2 Arena documentary.

Meanwhile he has represented Jamaica at Carifesta, taken a course from the School of Drama, and consistently carried his poetry into the community through readings in youth clubs.

He talks fluently and rapidly, ever willing to reflect on the culture out of which his poetry is born or reason about alternatives to Jamaica’s partisan party politics, which resulted in 800 deaths during the last election. He is more guarded about himself.

Growing up in Jones Town, in Western Kingston, he started writing around the age of 13, inspired by his immediate surroundings, “the contradictions within the system, the tribalism, the bombings, the bad housing…”. Like many other youths he suffered what he describes as “tenement instability”, moving from one yard to another, from town to country and back again. Mikey Smith was raised “ghetto style” but qualified his comment as quickly as he’d made it.

“When I say ghetto style I don’t want it confused with any damn romanticism. There is a tendency within the press to feel that one of the basic characteristics of a reggae artist should be ghetto, along with herbs and Rasta, and nothin’ nuh go so. If you are oppressed and dispossessed you will naturally react to the social injustice around you, whether you are Rasta, semi-dread or baldhead.”

The “corner culture” of downtown Kingston and the harsh realities of a subsistence, growing up in yards “which part everybody think dem better off then de other” forms the cornerstone of his writing and he recognises in higglers and vendors, a society in crisis. ‘Deliverance’, as promised by Prime Minister Eddie ‘CIA-ga’ is not at hand.

“It’s jus’ limited perceptions of progress. The Government’s new thrust for tourism means more tourist come, more hotels go up and as far as they’re concerned that’s progress…

‘Deliverance’ as such. Jamaica is becoming a pawn of the United States; you walk through Jamdown and it’s hamburger and ice cream stands – Crazy Jim or Kreemy King – everyone’s ‘getting’ down.”

With deep roots in Jamaica’s oral tradition, Smith’s poetry combines militant concern with a fascination for different styles of communication; from the DJ at the sound system dance to the rhetoric of the preacher or the politician, from proverbs, riddles or nursery rhymes to the inspirational example of the Pink and Black store in downtown Orange Street where, from inside the store, a man would chant, “Come een, come een, come buy-up, buy-up; but no come een an tief-up, tief up, for we beat-up, beat-up.”

His fascination with Jamaican creole and its rhythmic patterns correspond to a deep respect for Louise Bennett aka Miss Lou, Jamaican folklorist and linguist.

“I consider Louise Bennett to be the mother of the young dub poets; Linton, Oku, Mutabaruka and myself. She has really stood up against colonial values, in which it is understood that real communication would have to be in the Queen’s English. To really communicate and be understood by all, you have to communicate in the language of the oppressed and dispossessed people you’re dealing with.

“She elevated the language so the people can take pride in and a feeling of positiveness about themselves.”

In the Jamaica of 1982 it’s the DJs who carry the swing. Mikey Smith, like Muta, would like to see them play a more positive role but is not optimistic.

“There’s a lacking of cultural awareness, of their responsibility to the community. Not understanding the reality, they’re just giving off all these negative images of women; where one feels that the motivating force within the ghetto environment is one of sexuality and that man have fe jus’ get up and screw a woman and that’s all.

“The woman is being seen as a contributor to man’s social frustration and is being kept down, when the women have within themselves a lot of frustrations that the system has handed out. The women have to play an important stabilising role within yard culture; she have to be economist, she have to be mother; she have to father; she have to be hustler and pon top a dat she have to be a WOMAN.

“That’s a lotta strain, and when the man in turn can’t realise all of what the sista or dawta is goin’ through then he’s jus’ fucked up in the head. He’s comin’ like a crab; full of shit and nothin’ else.”

“The DJs either get caught up in the star trip or lose their early impact through not having consistency, like Bob Marley had. Many actually started out doing very authentic stuff, trying to communicate to a wider community, but as soon as the cameras and pens start then the message stops and they degenerate. I have to guard myself, so that I don’t get caught in the old trap of the El Dorado.”

Ironically, though the poetry of Mikey Smith, Oku Onuora and Mutabaruka enjoys literary and academic acclaim in Jamaica and has gained wider acceptance through their appearances at events like Reggae Sunsplash they, like many other local artists, will have “to go a foreign” and create an international impact before reaching a mass audience at home.

Though their often harrowing and revolutionary vision of Jamaica is well within the tradition Marley spearheaded, they could suffer, as the Gong did, by being at odds with the local media’s fondness for banning the controversial. Mikey is less convinced by the system’s sudden adoption of Marley and is concerned that the deep, well-founded respect for him is being exploited.

“When the system is saying, ‘See it there, we elevate Rasta, we give Rasta the Order of whatever and now he’s a gentleman’. For them to give that sanitation is just pure hypocrisy. The rebel is being incorporated into the system that he never really stood for.

“Anytime you see the system and these hurry-come-up, fly-by-night people start to jump up and say ‘Yeah! Yeah! This is our artist’, you know there’s sump’n kinda wrong, ‘cause when alive the artist was opposed to certain tings. Their awakening to Bob Marley is since his death so them did dead all along.”

At present it’s in Brixton rather than Kingston that Mikey is hailed with shouts from the youth of “Bwoy, mi cyaan believe it” and the growing sense of community appreciation he experienced on his last trip to England will be boosted by the release of his album.

Enthused by the energy and commitment of Dennis Bovell and others on the record, Mikey is convinced that his JA experience meeting the UK sound gives the album “a unique cross-over character, creating a new dimension” but he is aware that the choice of rhythms at times induces a rhythmic progression alien to his poetry, forcing him to lose some of his Jamaican-ness and sound, ironically, sub LKJ.

But ‘Mi Cyaan Believe It’ contains nine universal classics of dub poetry at its wicked, incisive, visionary best and for proof just take in the crucial ‘Trainer’, included on NME’s Mighty Reelcassette.

Mikey Smith plans to return this month for readings to coincide with the LP’s release. He was amused at the thought of the approaching winter and our conversation returned to the English literature he was taught at school, and how at long last he might be able to comprehend all those poems about “daffodils and snow – you know dem weh deh?”

Michael Smith 14 September 1954 – 17 August 1983