19 April 1797

Mungo Park: Travelling with the slave coffle

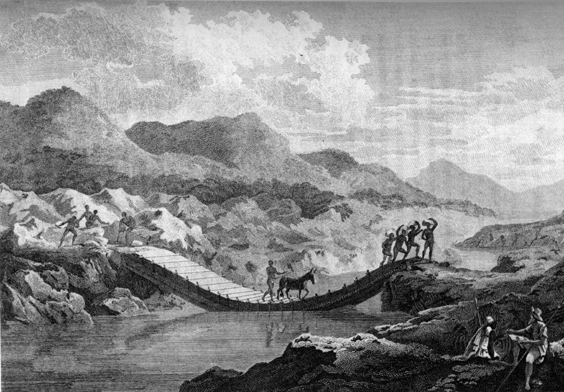

engraving of a slave coffle

IN THIS excerpt from Travels in the Interior of Africa, Mungo Park describes the composition of a slave coffle, which includes merchants, free men, their wives and domestic slaves, a schoolmaster, thirty five slaves for sale, and six Jilli keas – singing men – who served to keep spirits up as well as entertaining hosts along the route.

“The long-wished for day of our departure was at length arrived, and the Slatees (black merchants) having taken the irons from their slaves, assembled with them at the door of Karfa’s house where the bundles were all tied up, and every one had his load assigned him. The coffle, on its departure from Kamalia, consisted of twenty-seven slaves for sale, the property of Karfa and four other Slatees; but we were afterwards joined by five at Maraboo, and three at Bala, making in all thirty-five slaves.

The free men were fourteen in number, but most of them had one or two wives and some domestic slaves, and the school- master, who was now upon his return for Woradoo, the place of his nativity, took with him eight of his scholars, so that the number of free people and domestic slaves amounted to thirty-eight, and the whole amount of the coffle was seventy-three. Among the freemen were six Jilli keas (singing men), whose musical talents were frequently exerted either to divert our fatigue, or obtain us a welcome from strangers.

When we departed from Kamalia we were followed for about half a mile by most of the inhabitants of the town, some of them crying, and others shaking hands with their relations who were now about to leave them; and when we had gained a piece of rising ground, from which we had a view of Kamalia, all the people belonging to the coffle were ordered to sit down in one place, with their faces towards the west, and the townspeople were desired to sit down in another place, with their faces towards* Kamalia. In this situation the schoolmaster, with two of the principal Slatees, having taken their places between the two parties, pronounced a long and solemn prayer; after which they walked three times round the coffle, making an impression on the ground with the ends of their spears, and muttering something by way of charm. When this ceremony was ended, all the people belonging to the coffle sprang up, and without taking a formal farewell of their friends, set forwards. As many of the slaves had remained for years in irons, the sudden exertion of walking quick with heavy loads upon their heads, occasioned spasmodic contractions of their legs, and we had not proceeded above a mile, before it was found necessary to take two of them from the rope, and allow them to walk more slowly until we reached Maraboo, a walled village, where some people were waiting to join the coffle.

Here we stopped about two hours to allow the strangers time to pack up their provisions, and then continued our route to Bala, which town we reached about four in the afternoon. The inhabitants of Bala, at this season of the year, subsist chiefly on fish, which they take in great plenty from the streams in the neighbourhood. We remained here until the afternoon of the next day, the 20th, when we proceeded to Worumbang, the frontier village of Manding towards Jallonkadoo. As we proposed shortly to enter the Jallonka wilderness, the people of this village furnished us with great plenty of provisions; and on the morning of the 21st we entered the woods to the westward of Worumbang.

After having travelled some little way, a consultation was held whether we should continue our route through the wilderness, or save one day’s provisions by going to Kinytakooro, a town in Jallonkadoo. After debating the matter for some time, it was agreed that we should take the road for Kinytakooro; but as that town was a long day’s journey distant, it was necessary to take some refreshment. Accordingly, every person opened his provision-bag, and brought a handful or two of meal to the place where Karfa and the Slatees were sitting. When every one had brought his quota, and the whole was properly arranged in small gourd shells, the schoolmaster offered up a short prayer, the substance of which was, that God and the holy Prophet might preserve us from robbers and all bad people, that our provisions might never fail us, nor our limbs become fatigued.

This ceremony being ended, every one partook of the meal, and drank a little water; after which we set forward (rather running than walking) until we came to the river Kokoro, a branch of the Senegal, where we halted about ten minutes. The banks of this river are very high; and from the grass and brushwood which had been left by the stream, it was evident that at this place the water had risen more than twenty feet perpendicular, during the rainy season. At this time it was only a small stream, such as would turn a mill, swarming with fish; and on account of the number of crocodiles, and the danger of being carried past the ford by the force of the stream in the rainy season, it is called Kokaro (dangerous). From this place we continued to travel with the greatest expedition, and in the afternoon crossed two small branches of the Kokoro. About sunset we came in sight of Kinytakooro, a considerable town, nearly square, situated in the middle of a large and well-cultivated plain. Before we entered the town we halted, until the people who had fallen behind came up.

During this day’s travel, two slaves, a woman and a girl belonging to a Slatee of Bala, were so much fatigued that they could not keep up with the coffle; they were severely whipped, and dragged along until about three o’clock in the afternoon, when they were both affected with vomiting, by which it was discovered that they had eaten clay. This practice is by no means uncommon amongst the Negroes; but whether it arises from a vitiated appetite, or from a settled intention to destroy themselves, I cannot affirm. They were permitted to lie down in the woods, and three people remained with them until they had rested themselves; but they did not arrive at the town until past midnight, and were then so much exhausted that the Slatee gave up all thoughts of taking them across the woods in their present condition, and determined to return with them to Bala, and wait for another opportunity. As this was the first town beyond the limits of Manding, greater etiquette than usual was observed.

Every person was ordered to keep in his proper station, and we marched towards the town in a sort of procession, nearly as follows. In front, five or six singing men, all of them belonging to the coffle; these were followed by the other free people; then came the slaves, fastened in the usual way by a rope round their necks, four of 272 park’s travels in them to a rope, and a man with a spear between each four ; after them came the domestic slaves, and in the rear the women of free condition, wives of the Slatees, etc. In this manner we proceeded until we came within a hundred yards of the gate, when the singing men began a loud song, well calculated to flatter the vanity of the inhabitants, by extolling their known hospitality to strangers, and their particular friendship for the Mandingoes. When we entered the town we proceeded to the Bentang (a stage serving as a kind of town hall), where the people gathered round us to hear our dentegi (history); this was related publicly by two of the singing men; they enumerated every little circumstance which had happened to the coffle, beginning with the events of the present day, and relating everything in a backward series, until they reached Kamalia. When this history was ended, the master of the town gave them a small present, and all the people of the coffle, both free and enslaved, were invited by some person or other, and accommodated with lodging and provisions for the night.”