05 May 1980

Policemen hurt in night of violence

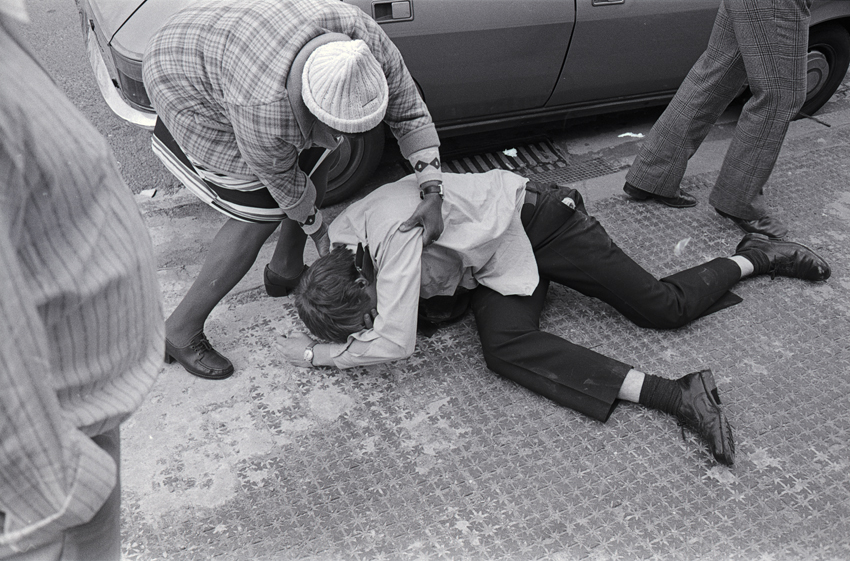

A WOMAN OFFERS A HELPING HAND TO AN INJURED POLICEMAN : Photo © Derek Bishton

ON THE Spring Bank Holiday 1980 (May Day) John Reardon and I were working at the Sidelines office in Grove Lane. There were a few people on the corner opposite where the local betting shop was doing good business. Suddenly a police panda car screamed to a halt outside the shop and two policemen attempted to arrest a young black man. A crowd quickly gathered. We were watching from the upstairs window of our building. The crowd surrounded the policemen who were holding their suspect and moments later the two police lay on the floor and the crowd melted away.

This is the way the following day’s Evening Mail (May 6, 1980) reported the incident under the headline ‘Policemen hurt in night of violence’:

“Two police constables were lying battered and bruised in hospital today after a brutal attack on them nearly turned into a major riot.

The night of violence ended with an angry mob of 200 of the sizeable black community in the Handsworth district of Birmingham surrounding a local police station and threatening to storm it.

Coloured people were jeering, hurling abuse and pelting stones – and only heavy police reinforcements prevented the Thornhill Road police station being overrun.

The drama began less than an hour earlier when police constable Nicholas Chandler, 24, and 20-year-old Ian Brown were kicked and beaten unconscious.

After one youth had been arrested in connection with a burglary at an Indian club in Soho Road, the constables tried to question a suspect in Grove Lane, a quarter-of-a-mile away.

Trouble flared as the officers tried to detain the teenager and fighting broke out with other youths.

A large number of people poured out of a nearby betting shop and as the constables were battered to the pavement, onlookers threw bricks and aimed kicks at them.

Within minutes, major police reinforcements were met by an angry mob who tried to prevent them taking the unconscious officers to safety. Stones were thrown at police cars as tempers erupted.

Today PC Chandler was in Dudley Road Hospital recovering from a broken collarbone, fractured ribs and internal bleeding. PC Brown was in the same hospital with severe concussion.

Police from all over Birmingham eventually persuaded the crowd to disperse.

Today a man was appearing before city magistrates accused of attempted robbery. A man and a woman were also due in court charged with wounding.”

The woman was Myrtle Edwards, a Jamaican-born hospital worker, who along with her two sons was arrested and charged with assaulting the two policemen, who had stopped one of the sons and tried to take him away on a burglary charge. In fact, it turned out to be a case of mistaken identity – all black men look the same to rookie 20-year-old white probationer coppers. They should have checked more carefully before they attempted to detain him.

There were a number of glaring inaccuracies in the Evening Mail report. Although neither John or I actually saw the assault on the policemen (it happened while we were running downstairs from our office and crossing the road) some local people tried to help the injured men, as my photograph shows. When the police reinforcements arrived, John was threatened by a senior officer and told not to take photographs (a request we both ignored).

When the road was finally flooded with police cars and uniformed and non-uniformed officers, the young man who was the original suspect – who had been en route to his mother’s house for a family meal – was dragged from the family house, along with his brother and their mother, who were all protesting their innocence. No stones were thrown. No blows exchanged.

Later, when the case came to trial, the judge criticised the policemen because they had broken just about every rule in the book and provoked a near riot. But he told Mrs Edwards: “Two policemen have been injured and someone must pay.” All three members of the family received six-month custodial sentences. Mrs Edwards, a regular attender at the Soho Road Baptist Church, told me after leaving prison: “The Lord knows I am innocent and I leave it to the Lord to deal with the wicked.”

This episode was the most blatant example that I witnessed first hand of the blind, racist response that characterised the way the police behaved in Handsworth at that time towards black people.