13 February 2000

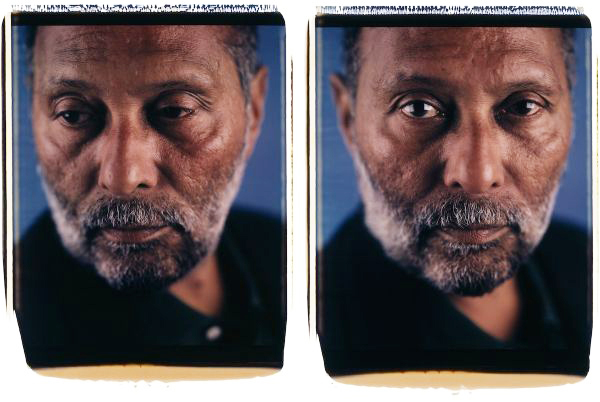

Professor Stuart Hall’s Desert Island Disks

PROFESSOR STUART HALL was the first Black academic castaway on the BBC Radio4 programme Desert Island Disks where guests are invited to choose eight pieces of music they would take with them if they were cast away on a desert island. Hall, who died in 2014, was born in Jamaica and became a leading cultural theorist, sociologist and campaigner in the UK. He was widely acknowledged as the founder of Cultural Studies which, under his guidance, insisted on taking popular, low-status cultural forms seriously and tracing the interweaving threads of culture, power and politics that underpinned their meaning. Here are his music choices and some of his comments from the programme first broadcast in February 2000.

On Britishness: I think the British have a future only if they can come to terms with the fact that Britishness is not one thing and has never been one thing. There have been a million different ways of being British and there have been a million different struggles about Britishness which only retrospectively are then smoothly accommodated into the story as if it’s unfolding seamlessly from beginning to end, but it isn’t like that. If you think of last year (1999). . . first of all the celebration of the Windrush Arrival, which is 50 years since the first post-war migrants. On the other hand there is the MacPherson inquiry into the death of Stephen Lawrence. And it seems to me that Britain is facing these two possibilities as an alternative future. I want the British to consciously move, in a more concerted and open way, towards a more cosmopolitan idea of themselves.

On first listening to modern jazz: As a young student in Jamaica I listened to a lot of kinds of music, my brother played 40s American swing, we used to play Jamaican folk music, but none of that music belonged to me. The first musical sound that I felt really belonged to me was the sound of modern jazz. It opened up a new world. I knew that it was a world from the margins. It opened up the possibility of really experiencing modern life to the full and it formed in me the aspiration to go and get it, wherever it was.

Disc One: Miles Davis – Sid’s Ahead

On colour, class, family: Curiously, I’m the blackest member of my family. That’s an odd thing to say but, you know, these mixed families produce children of all colours. And in Jamaica the question of exactly what shade you were, in Colonial Jamaica, that was the most important question because you could read off class and education and status from that. I was aware and conscious of that from the very beginning. My family was quite mixed. My father was from the lower middle class, a country family, respectable, his father was a chemist, but not much money. My mother had been adopted by her uncle and aunt and lived most of her life on a small plantation very close to the English, indeed her cousins were educated in England, they never came back. She had grandparents who were white. And she brought into our family all the aspirations of a young plantation woman . . . Nothing Jamaican was really any good, everything was to aspire to be English, to be like the English, or like the Americans. The ideals in our family were somewhere else. I had this tension throughout my life between what I thought I was – young, bright, Jamaican (Jamaica with aspirations for a growing independence movement, to be free one day) – and this refusal of my family to live in that world at all . . .

Disc two: Bob Marley – Redemption Song

This is the sound that saved a lot of second generation Black West Indian kids from just, you know, falling through a hole in the ground, because they didn’t know who they were, never been taught that they had a slave background, never been taught that they came from Africa. The British didn’t want them and suddenly in their transistor sets they heard this voice from a place called Trench Town that became universally known throughout the world; it’s an astonishing thing.

On arriving at Oxford, aged 19, in 1951: My mother delivered me in a felt hat and a check coat, with a steamer trunk, to my scout in Merton College, Oxford. Heaven knows what he made either of her, or of us, or of me. I don’t know what I ever did with the steamer trunk. I think I persuaded him to take it into the basement and just lost it.

What I realised the moment I got to Oxford was that someone like me could not really be part of it. I could make a success there. I could even be part accepted into it. But I would never feel it was my place . . . It is the summit of something else, it is distilled Englishness, it’s the peak of the English education system. An Oxford education works only because you already know 90 per cent of it in your bones. You absorb the culture. You can’t learn those things. I could study English literature, but the cultural buzz that made each text live as part of a whole way of life, was just not me, just not me . . .

Disc three: Johann Sebastian Bach, Brandenburg Concerto No. 2 in F major

What to do with the frustration that had built up in Jamaica? What I realised in Oxford was that I couldn’t really escape it, I had to go through it, I couldn’t just leave it behind. I couldn’t become someone else. It was a period really of coming to terms with myself.

I became involved in politics, with people in the Labour Party and young communists and people from the third world. I played in a group at Oxford, which kind of saved my soul some of the time. And we debated furiously . . .

Hungary and Suez: That space in politics which was defined on the one hand by the Soviet invasion of Hungary, which told us all one needed to know about the totalitarianism of that system, and on the other hand the invasion of Egypt which I thought told us that the imperial legacy was not dead, as people were saying. It hadn’t gone away, it was a very long-lasting reactional response in the English mentality and one had to struggle against it, not just think that it was going to fade away with the winds of change. Somewhere in between, the idea of a democratic, socialist anti-imperial politics was born. And that’s the moment of the New Left.

We started in Oxford a small journal called University of the Left Review, and then there was another journal started mainly by people who had left the Communist Party called The New Reasoner and these two journals came together to form New Left Review. People who ought to have edited it . . . important political people like the historian E P Thompson, had really exhausted themselves in the struggles to found these journals, so me in my early 20s found myself editing these grand figures . . .

The British Film Institute: I had a friend, Paddy Whannel, who was the education officer at the British Film Institute. There was no teaching of film in the universities, there was no formal study of film at all . . . We started to do lectures on both film as a serious art form but also on popular cinema. And we tried to write for teachers who wanted to teach this stuff in classrooms but didn’t know how on earth to do it. We decided to write a how to do it book called The Popular Arts, but this was really an excuse for reading popular novels and looking at television and listening to rock music and listening to jazz and steeping oneself in popular culture. And one of the things I discovered during that period was the voice of Billie Holiday. . .

Disc four: Billie Holiday – I Cover The Waterfront

Why cultural studies? This was the period of the coming of television, it’s the coming of youth culture, of Rock Around the Clock. It’s just the explosion of the 20th century in a pre-20th century society. And we wanted to say that school was a place in which you could reflect on life as you know it . . . it’s about you and about the life that you are living and about the changes that are going on in front or you.

Really there isn’t just one kind of literary or cultural value – there are many kinds. You don’t go to Shakespeare for the same things you go to Tolstoy or George Eliot. These are different values. You might say that certain works express these values and meanings at a level of complexity and refinement — that’s one thing, that’s quite true . . . High culture is really the very selective appropriation of a certain limited range of cultural forms and the investment in that of a kind of social value: it’s not that people are really responding to what there is in King Lear, they’re appropriating Shakespeare as a kind of badge of I’m an educated person.

On Who Wants to be a Millionaire? There are limits to my taste. (laughs) But if you ask me should we study it, yes we should study it. It comes right out of everything that has happened in economic life in Britain and the western world in the last 10 years. It’s the Ur-story of the free market . . .

Centre for Contemporary Cultural Studies, Birmingham, 1970s: Marvin Gaye stands for all the music I listened to then. It was a very heady time. We were involved in building this new area of study. I was working with very bright graduate students. We were making it up as we went. There was no discipline to study, so it was hardly a relationship of teacher and taught. They were my friends, my students, my apprentices. I was just married. My wife was a historian, very involved in the early feminist movement. And one of the things we would do is dance.

Disc five: Marvin Gaye – I Heard It Through The Grapevine

The multicultural society: Salman Rushdie said, “mixture is how newness enters the world. . .” Who wants to be the same throughout time? What you want to do is be different throughout time. It’s a process of becoming, not of being . . . it’s routes, the various pathways that brought you to where you are that matter . . . Society is kind of drifting into this, it’s what I call multicultural drift. But what it is not yet able to say to itself is “difference is good, there’s something positive about people being different from oneself” . . . I think we’re on the edge of that and I think that what threatens is the idea that modernity is too difficult for us: let us withdraw behind a little England citadel — that’s on the cards too. I think Britain is at an important historical turning point.

The minorities are just on the edge of feeling that they’ve stopped being people from somewhere else, who didn’t have anything intrinsic to do with English or British history. They’re just on the edge of feeling, we have been a part of this story from the beginning. . . The teaching of history in schools has to go back and reread the history of empire, not as some sort of dangling appendage out there which you can or can not know about, but as something which is absolutely deep at the heart of English identity.

My wife [Catherine Hall] works on the connection between England and Jamaica in the 19th century. Every English middle class provincial abolitionist family had a connection with Empire, knew about the Empire, watched lantern slides about it, read about it, heard it preached about in the pulpit. It’s an insidepart of Englishness. . . It’s not a question of: Are you nice to us? It’s a question of: We are part of you. And there could come a time when Britain would be proud of saying this is, as much intrinsic to who we are as, you know, 1066 . . .

I’ve always kept going back and listening to the music of my youth. But I like to hear that music rephrased in a modern idiom.

Disc six: Wynton Marsalis Quartet – Caravan

The reason why I’m interested in culture is because culture is the meanings that are inscribed in our actions, in our behaviour, in our every day conduct. And when ideas take root in everyday practice, not a matter of consciously being good to the other, but naturally, organically in our actions, we just think that difference is what is really exciting about the world.

On devolution: This is an interesting moment, because curiously, just as the British are giving up on Britishness, (Scotland was granted its own Parliament in 1999) we are just discovering it . . . There’s a very long time, nearly fifty years, where very few people from the Caribbean or from Asia would ever dream of calling themselves British, even in a hyphenated way, and it’s just happening now. This is one of the ironies, the quirks of history, that just as you brought down the flag of Empire, we came to discover the Mother Country, and just as you desert Britishness, we discover that we are really pretty British after all: Black and British.

I suppose when I was 19 or 20, I would say Miles Davis put his finger on my soul. The various moods of Miles Davis have matched the evolution of my own feelings. They continue to be a regret for the loss of a life that I might have lived but didn’t live. I could have gone back to Jamaica, I could have been a Caribbean person. I’m not that any more. I can’t ever be English in the full sense, though I know and understand the British like the back of my hand. The uncertainty, the restlessness and some of the nostalgia for what cannot be is in the sound of Miles Davis’s trumpet.

There’s a funny way in which, because I can never go home again, Jamaica is a kind of fantasy island for me. When I go there I love it, I know what it’s like, but it’s not me any longer.

Disc seven: Miles Davis – I Waited For You

On things to be proud of: I felt I was a good teacher. I loved my time with the Open University. When I left the Centre [for Cultural Studies] I wanted to go, not to a place where I taught very bright students who had already had many of the opportunities, I wanted to take those ideas into teaching people who had no formal educational background. I love being a teacher.

I love working collectively with people. I work in Black arts organisations now, with filmmakers and people in the visual arts. I’m a sort of enabler of other people doing things. I work best collectively. I work best with a group. So I don’t think of these with a sense of personal achievement really. I feel as if my life is a journey which many people have taken, it’s a sort of a paradigm of all those people who got on the Windrush and came to try and find another life . . .

I want music that will take my soul and make it soar. I’ve started to listen to opera. I never wanted to go to opera very much. I didn’t like the ambiance so much, all those heads nodding through Don Giovanni. But I love the music, the archetypal, the Verdi and Puccini.

Disc eight: Puccini – Un bel di vedremo (One fine day) from Madame Butterfly

Choosing a desert island book: The book is a problem because I would be terrified of running out of things to read. . . I want to take a book where the language is so complex and the sensibility and feelings are so refined that a paragraph would take a whole day, and that is Henry James’s Portrait of a Lady .

Luxury item: The luxury I want is my grandson Noah. He’s only 14 months . . . we have long conversations but he doesn’t yet speak. But I know you’re not going to allow that. So I’d better take a piano and I’ll really, for the first time, teach myself to play the piano properly.

If you could only save one disc from the waves: Miles Davis – I waited for You

Stuart Hall was born in Jamaica on February 3, 1932. He died in London on February 10, 2014.

With thanks to https://www.opendemocracy.net/shinealight/stuart-hall/castaway-stuart-hall-in-his-own-words