08 December 1977

Shades of Grey: A report on Police-West Indian Relations in Handsworth

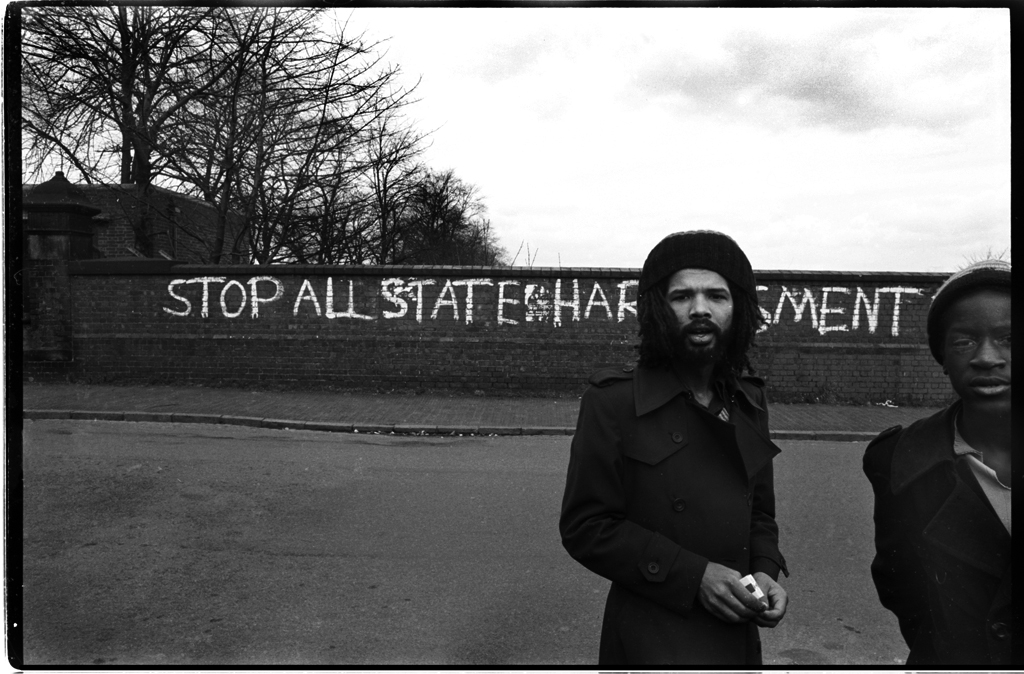

Two young Rastas in front of a slogan saying ‘Stop all state harassment’, Handsworth, 1978. ©derek bishton

JOHN BROWN, a lecturer at the Cranfield Institute of Education was invited to study policing methods in Handsworth in the summer of 1977 following fears expressed by many community leaders that police were routinely using ancient laws enacted in the period of the Napoleonic wars to stop and search young black men for no other reason than that they were young and black. Many people feared that these tactics would lead eventually to violent retaliation.

Brown had been identified following a letter from Clare Short, then director of AFFOR, to West Midland Police expressing concern on behalf of a wide range of community organisations. Her letter was composed in the late summer of 1976 when a number of homeless young Rastas had set up squats in empty houses in various parts of Handsworth. Complaints from the mainly white residents about the noise – because the new residents did like to play their music loud and often at night – led to an almost continuous police presence. It was a crazy moment. There were confrontations on the streets on a daily basis.

So, into this pressure cooker situation stepped John Brown. In May and June 1977, he spent time with various community groups, including Handsworth Law Centre, Harambee, Birmingham Community Relations Council, Afro Caribbean Club and Bing’s Club and the policemen at Thornhill Road police station in Handsworth. He produced a modest-looking 45-page report called Shades of Grey, typed on a manual typewriter, duplicated using a Roneo stencil printer and bound with a white plastic strip.

Brown was Head of the Department of European Languages and Institutions at Cranfield Institute of Technology and had spent time in the Leeward and Windward Islands as a University of West Indies tutor. He had also written several articles for the Police Journal.

His report is a curious mixture of highly subjective description, a few crime stats, and a large helping of common sense racism. He writes: “. . . it becomes clear that the most serious police problems relate to crimes of violence against persons and personal property, mainly committed . . . between dusk and the early hours and mainly by a particular group – some 200 youths of West Indian origin or descent who have taken on the appearance of followers of the Rastafarian faith by plaiting their hair in locks and wearing green, gold and red woollen hats.”

“Many of the couple of hundred ‘hard core’ Dreadlocks who now form a criminalised sub-culture in the area live in squats. Almost all are unemployed. And apart from the specific crimes for which they are responsible, they constantly threaten the peace of individual citizens, black brown and white, whilst making the police task both difficult and dangerous, since every police contact with them involves the risk of confrontation or violence.” (1)

This was to be one of the enduring urban myths of the report – the 200 hard core Dreads who transition into the new folk devils. “It came to be believed by people that conflict between young blacks and the police was the essence, the very substance of the problem of race, for the country as a whole,” as Paul Gilroy notes “In the early period, people had thought of Black settlers and their children as rather predisposed to be law-abiding,” says Gilroy. Shades of Grey played a key role in creating the popular sentiment that Black people were much more predisposed to criminality, and that it was their culture which produced this behaviour. ‘It’s their family life which sanctions it. It’s the conflict between generations which reproduces it as a pathology, and we, good noble British people, are at a loss to know how to intervene in that cycle of criminal pathology’.” (2)

Brown goes out with a constable to experience first-hand the work of the uniformed branch units. “Impressions of place and people grow into patterns: of abrupt transitions from red-brick affluence to gutted desolation; of street upon street going to seed; of ageing whites, particularly old ladies with bowed backs, tired faces, thin shopping bags; of busy Indians, their ladies in smart saris, opening more shops in the Soho Road; of knots of young West Indians against broken fences, shouting abuse and jerking fingers as the panda passes.”

The constable he is driving with says: “The worst of it here is West Indian. It’s nothing to do with colour though. I don’t believe I’m prejudiced like that. Most of the older West Indians I know, they’re no trouble. The trouble’s the young ones, say 10 to 25. . . To my mind the trouble begins and ends in the homes.” (3)

There are so many troubling, racist sentiments in these two paragraphs. From the use of the word ‘stock’, with its animal associations; his description of the stereotypical ‘victim’- the little, vulnerable, old white lady with her ‘thin’ shopping bag; his characterisation of the ‘busy’ Indians; to, of course, the abusive Black kids lazing around on ‘broken’ fences giving him the finger. Then, the coup de grace: a quote from a good, honest copper. “To my mind the trouble begins and ends in the homes.”

These words of wisdom come from the mouth of a 22-year-old, barely out of his probationary period. He has been hot-housed in the insular, all white environment of Thornhill Road police station where other adrenalin-fueled young men and women – many of them even younger than him – are ready to fight the good fight. His insights are fatally flawed but they are given canonical status by Brown.

Of the 91 constables stationed in Handsworth when Brown paid his visit, 11 were women and nine probationers with an average age of 20. Invoking the casual sexism of the times, Brown notes: “The youngest of the (very attractive) bunch was 18-and-a-half, a slim, neat girl who had just finished her first week of service on night duty.” She had been involved in an incident where two young Dreads had been pursued on suspicion of stealing a car. At one point she found “a six-foot Dreadlock coming at her. She dived and held him until the other two officers came up, subdued and arrested him after a violent struggle. So, after her first week, she felt she belonged.” (4)

As a set of stereotypes wrapped up in the comfort blanket of common sense racism, Brown’s report is master class. Its impact was enormous. Local and national newspapers devoured the image of 200 hard-core Dreads terrorising little old white ladies and repeated it endlessly. Even a couple of years later, a reporter for The Daily Telegraph wrote: “Handsworth not long ago a racial hell hole, where the community was terrorised a few years ago by 200 Dreadlocks, rootless squatting pseudo-Rastafarian young thugs.” (5)

The impact of Brown’s report was the subject of a forensic study by Paul Gilroy in The Empire Strikes Back where he traced the post war development of police theorizations of ‘alien blackness’ as black criminality to “show where the filaments of racist ideology disappear into the material institutions of the capitalist state.”

“What is at issue here is not therefore whether there are ‘illegal immigrants’, ‘muggers’, or ‘criminally inclined Rastafarians’ in ‘tea cosy hats’, but the universality with which the authorities apply these terms to all Black people, while ignoring the level of ‘criminal’ violence against Blacks themselves.”

Gilroy sums up Brown’s principal achievement as “the transposition of the debate about black crime and politics into the key of black culture, indexed by the ‘pathetic West Indian family’. Here, the parents were incapable of exercising authority correctly and this caused family breakdown, impelling the offspring – already caught between two cultures – into gender-specific identity crises: the boys lapsed into criminality, whilst the girls whose cultural bastardy was confirmed by their unfeminine predisposition to violence, produced unplanned children and the cycle started anew.” (6)

The report’s most enduring theme was the separation of the real Rastafarian, from the criminal imposters – the wolves in sheep’s clothing – who were able to assume the appearance of the former. This was the great Catch-22 of Brown’s report: not all Rastas are hardened criminals, but it’s impossible to tell just by looking because they are indistinguishable from the criminal Dreadlocks. The logic of this distinction is, of course, that all Rastas are potential criminals.

(1) Shades of Grey page 3

(2) Paul Gilroy interviewed in Windrush by Mike Phillips and Trevor Phillips pages 304-5

(3) Shades of Grey page 28

(4) Shades of Grey page 10

(5) The Daily Telegraph 9 May 1980, Quoted by Gilroy in The Empire Strikes Back p162

(6) Police and Thieves , The Empire Strikes Back P145- 146

Note: The genesis of the Shades of Grey report lay in complaints made by Clare Short, then director of community agency Affor, to West Midlands police. Following discussions between Anthony Wilson, representing the Barrow Cadbury Charitable Trust, and the Deputy Chief Constable, Brown was invited to Handsworth at the end of May, 1977, to hear views of local community groups. In the end, Short was so concerned by Brown’s report she commissioned a second report, Talking Blues in which members of the black community related their experiences with the police.