05 January 1865

The Underhill Letter and the Morant Bay Rebellion

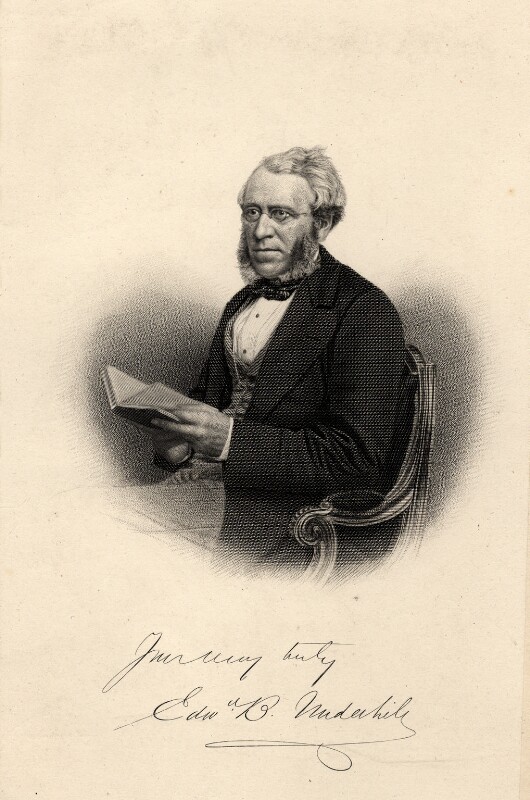

Edward Bean Underhill after Unknown artist, stipple engraving, late 19th century

© National Portrait Gallery, London

EDWARD BEAN UNDERHILL (1813-1901) was secretary of the Baptist Missionary Society from July 1849 until his death. He visited the Society’s centres in India, Ceylon and the Caribbean and wrote in great detail about his experiences. His The West Indies: their Social and Religious Condition was published in 1862, and the worsening economic conditions in Jamaica prompted him to write to the Colonial Secretary Edward Cardwell in January 1865. The letter, which catalogued the devastating effect of adverse weather and a complete reliance on sugar production, estimated that 340,000 Jamaicans were near starvation. The letter was widely circulated in Jamaica by Baptist missionaries and Governor Eyre blamed Underwood for causing the unrest that led to the Morant Bay Rebellion later the same year.

- UNDERHILL TO THE RIGHT HON. E. CARDWELL.

33, Moorgate Street, E.C.,

Jan. 5, 1865.

Dear Sir, — I venture to ask your kind consideration of a few observations on the present condition of the Island of Jamaica.

For several months past every mail has brought letters informing me of the continually increasing distress of the coloured population. As a sufficient illustration, I quote the following brief passage from one of them: — “Crime has fearfully increased. The number of prisoners in the penitentiary and gaols is considerably more than double the average, and nearly all for one crime — larceny. Summonses for petty debts disclose an amount of pecuniary difficulty which has never before been experienced; and applications for parochial and private relief prove that multitudes are suffering from want little removed from starvation.”

The immediate cause of this distress would seem to be the drought of the last two years; but, in fact, this has only given intensity to suffering previously existing. All accounts, both public and private, concur in affirming the alarming increase of crime, chiefly of larceny and petty theft. This arises from the extreme poverty of the people. That this is its true origin is made evident by the ragged and even naked condition of vast numbers of them; so contrary to the taste for dress they usually exhibit. They cannot purchase clothing, partly from its greatly increased cost, which is unduly enhanced by the duty (said to be 38 per cent, by the Hon. Mr. Whitelocke) which it now pays, and partly from the want of employment, and the consequent absence of wages.

The people, then, are starving, and the causes of this are not far to seek. No doubt the taxation of the Island is too heavy for its present resources, and must necessarily render the cost of producing the staples higher than they can bear, to meet competition in the markets of the world. No doubt much of the sugar land of the Island is worn out, or can only be made productive by an outlay which would destroy all hope of profitable return. No doubt, too, a large portion of the Island is uncultivated, and might be made to support a greater population than is now existing upon it.

But the simple fact is, there is not sufficient employment for the people; there is neither work for them, nor capital to employ them. The labouring class is too numerous for the work to be done. Sugar cultivation on the estates does not absorb more than 30,000 of the people, and every other species of cultivation (apart from provision growing) cannot give employment to more than another 30,000. But the agricultural population of the island is over 400,000, so that there are at least 340,000 whose livelihood depends on employment other than that devoted to the staple cultivation of the island. Of these 340,000 certainly not less than 130,000 are adults, and capable of labour. For subsistence they must be entirely dependent on the provisions grown on their little freeholds, a portion of which is sold to those who find employment on the estates; or perhaps, in a slight degree, on such produce as they are able to raise for exportation. But those who grow produce for exportation are very few, and they meet with every kind of discouragement to prosecute a means of support which is as advantageous to the Island as themselves. If their provisions fail, as has been the case, from drought, they must steal or starve. And this is their present condition. The same result follows in this country when employment ceases or wages fail. The great decrease of coin in circulation in Jamaica is a further proof that less money is spent in wages through the decline of employment. Were Jamaica prosperous, silver would flow into it, or its equivalent in English manufactures, instead of the exportation of silver, which now regularly takes place. And if, as stated in the Governor’s speech, the Customs’ revenue in the year gone by has been equal to former years, this has arisen, not from an increase in the quantities imported, but from the increased value of the imports, the duty being levied at an ad valorem charge of 12 per cent, on articles, such as cotton goods, which have within the last year or two greatly risen in price.

I shall say nothing of the course taken by the Jamaica Legislature: of their abortive Immigration Bills: of their unjust taxation of the coloured population; of their refusal of just tribunals; of their denial of political lights to the emancipated negroes. Could the people find remunerative employment, these evils would in time be remedied, from their growing strength and intelligence. The worst evil consequent on the proceeding’s of the Legislature is the distrust awakened in the minds of capitalists, and the avoidance of Jamaica, with its manifold advantages, by all who possess the means to benefit it by their expenditure.

Unless means can be found to encourage the outlay of capital in Jamaica in the growth of those numerous products which can be profitably exported, so that employment can be given to its starving people, I see no other result than the entire failure of the Island, and the destruction of the hopes that the Legislature and the people of Great Britain have cherished with regard to the well-being of its emancipated population.

With your kind permission, 1 will venture to make two or three suggestions, which, if carried out, may assist to avert so painful a result.

- A searching inquiry into the legislation of the Island since emancipation, its taxation, its economical and material condition, would go far to bring to light the causes of the existing evils, and, by convincing the ruling class of the mistakes of the past, lead to their removal. Such an inquiry seems also due to this country, that it may be seen whether the emancipated peasantry have gained those advantages which were sought to be secured to them by their enfranchisement.

- The Governor might be instructed to encourage, by his personal approval and urgent recommendation, the growth of exportable produce by the people, on the very numerous freeholds they possess. This might be done by the formation of associations for shipping their produce in considerable quantities; by equalizing duties on the produce of the people and that of the planting interests; by instructing the native growers of produce in the best methods of cultivation, and pointing out the articles which would find a ready sale in the markets of the world; by opening channels for the direct transmission of produce, without the intervention of agents, by whose extortions and frauds the people now frequently suffer and are greatly discouraged. The cultivation of sugar by the peasantry should, in my judgment, be discouraged. At the best, with all the scientific appliances the planters can bring to it, both of capital and machinery, sugar manufacturing is a hazardous thing. Much more must it become so in the hands of the people, with their rude mills and imperfect methods. But the minor products of the Island, such as spices, tobacco, farinaceous food, coffee, and cotton, are quite within their reach, and always fetch a fair and remunerative price, when not burdened by extravagant charges and local taxation.

- With just laws and light taxation, capitalists would be encouraged to settle in Jamaica, and employ themselves in the production of the more important staples, such as sugar, coffee, and cotton. Thus the people would be employed, and the present starvation rate of wages be improved.

In conclusion, I have to apologise for troubling you with this communication; but since my visit to the Island in 1859-60, I have felt the greatest interest in its prosperity, and deeply grieve over the sufferings of its coloured population. It is more than time that the unwisdom (to use the gentlest term) that has governed Jamaica since emancipation, should be brought to an end; a course of action which, while it incalculably aggravates the misery arising from natural, and therefore unavoidable causes, renders certain the ultimate ruin of every class — planter and peasant, European and Creole.

Should you, dear Sir, desire such information as it may be in my power to furnish, or to see me on the matter, I shall be most happy either to forward whatever facts I may possess, or wait upon you at any time that you may appoint.

I have, &c, ” Ed wd. B. Underhill.