23 April 1758

What the voyages of HMS Harwich reveal about the ‘instruments of empire’

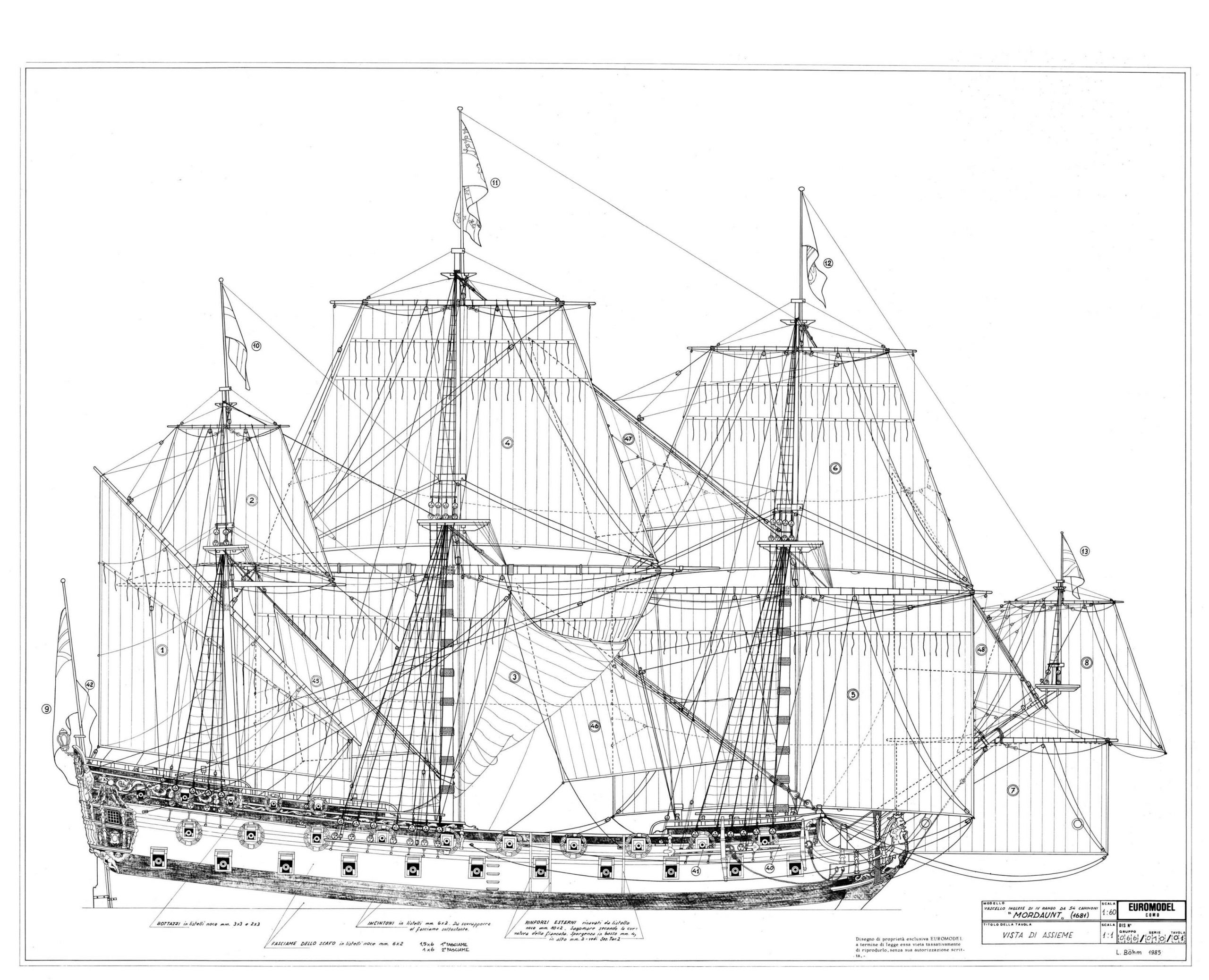

A naval plan of a fourth rate ship of the line similar to HMS Harwich

“AS ENGLAND pursued its campaigns in West Africa and the West Indies, its ships, sailors and soldiers traced the connections between the Jamaica garrison and the wider war. By their movements and actions, these instruments of empire bound the disparate regions of the Atlantic world to the slaving economy. The belligerent cruise of HMS Harwich offers a telling example,” writes Vincent Brown in his brilliant new book Tacky’s Revolt: The story of an Atlantic slave war.(1)

The Harwich, a fourth rate ship of the line bearing 50 heavy cannon, was commissioned by the Royal Navy in 1756, according to Brown. In 1758, the Harwich’s captain William Marsh assumed command of a small expedition which included HMS Nassau, HMS Rye and three smaller vessels, with orders to attack any French forts and settlements on the River Senegal or the coast of Africa.

The expedition was a response to the French expansion of trade with Africa. In 1753, they began building forts on the Gambia. According to British merchants, they were also stirring up the natives against them. The Royal African Company, who held the monopoly of the slave trade, had a line of fortified depots on the West Coast and it begged the British government to eliminate the potential threat from the neighbouring French settlements in Sénégal and in the island of Gorée.

So, the expedition led by the Harwich arrived at the mouth of the Senegal River on April 23. In spite of spirited resistance from the French and their African allies, the British ships bombarded the shore and by April 29 had landed 700 marines. On May 1, the French surrendered, giving up “all the forts, storehouses, vessels, arms, provision and every thing belonging to the company upon the River Senegal.” This included 92 pieces of cannon, 400 tons of gum, a great quantity of gold dust, nearly 50,000 dollars and a year’s supply of good for barter, in addition to 50 enslaved Africans and more than 200 other people. (2)

Buoyed by this, the fleet decided to attack the French naval station and slave barracoon at Gorée Island. However, the French response this time was more effective and after a two-hour exchange of cannon fire, the Harwich was badly damaged and the expedition was abandoned. The fleet retreated to the adjacent Gambia River. Most of the fleet was then ordered home, leaving only HMS Harwich and HMS Rye. After another bloody engagement at Allbreda, where the French enjoyed great support from the local African state, the Harwich was forced to withdraw after being heavily outnumbered by African soldiers. Brown reports that the Harwich then attended to protecting the slave trade along the Gold Coast, before departing Africa for the Caribbean, arriving in Jamaica on December 1, 1758.

Although the Harwich was deployed in the Caribbean to help protect Britain’s maritime trade, it was scarcely two years before it was called into action to help quell the slave insurrection led by Apongo (aka Wager) in Westmoreland in May 1760. On June 4, the Harwich sailed for Bluefields harbour from Kingston with 60 soldiers and 58 marines from HMS Cambridge, the flagship of the Caribbean fleet. Brown notes: “Most of the Harwich’s sailors and marines had a fresh memory of fighting West Africans. It had been a scant two years since their failed attempt on the French fort at Allbreda . . . The Harwich’s marines now combined with those from the Cambridge, more than 30 of whom had fought black soldiers at Guadaloupe. The Royal Marines, newly reorganised for the Seven Year’s War, had gained many of their first combat experiences fighting Africans, both enslaved and free.” (3)

- (1) Tacky’s Revolt: The story of an Atlantic slave war, Vincent Brown, Harvard University Press 2020. p83

- (2) cit p80

- (3) Cit p184